A Portrait of Lucia Pica

I’m very rebellious, not for the sake of it, but when I believe in something I will really defend it.

LP.

Paris, November 2018

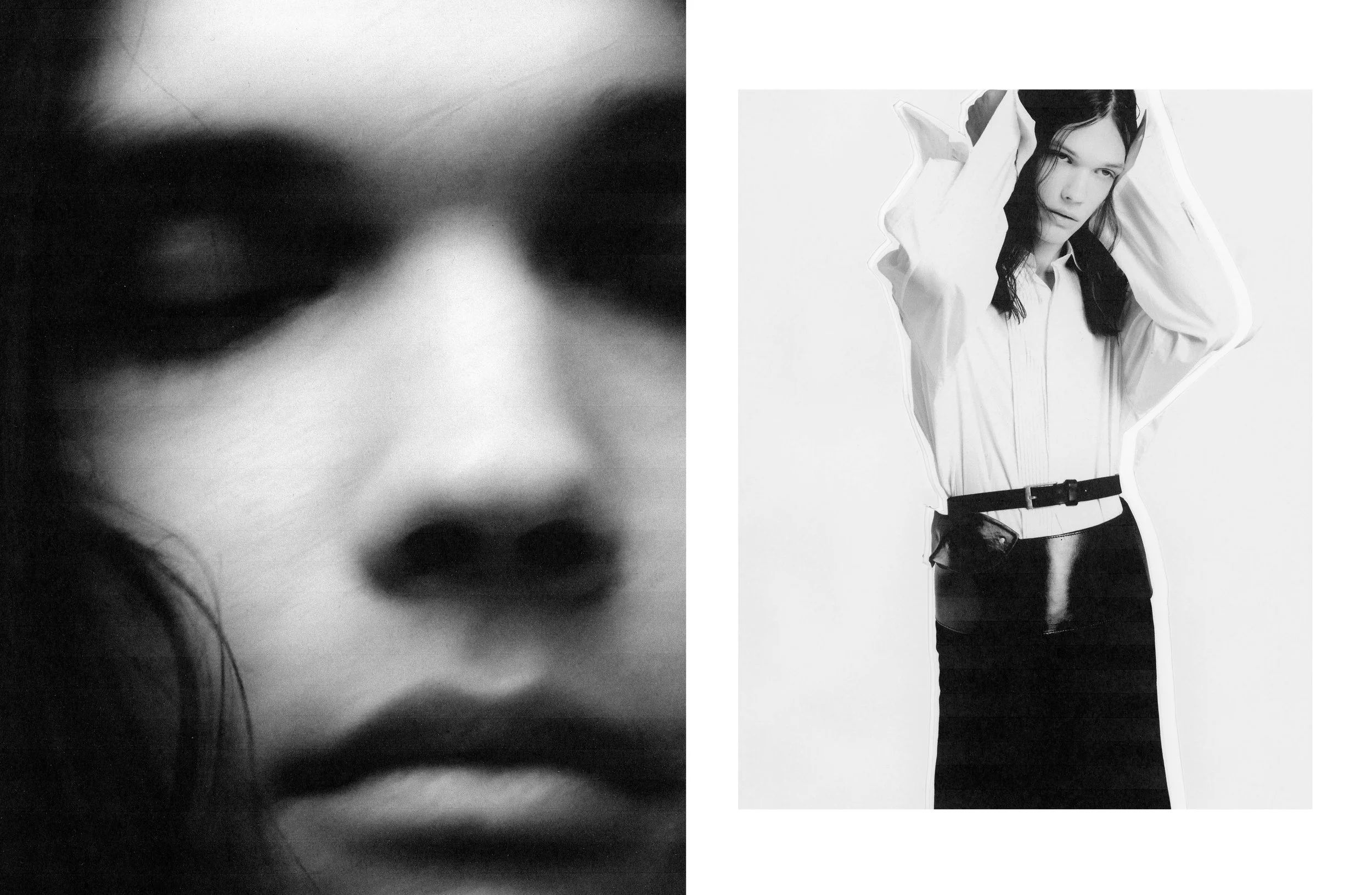

Appointed as Chanel’s Global Head of Make-Up and Color Design at the start of 2015, Lucia Pica is a luminous woman. Wearing a black tweed pantsuit with a dark red pussy bow blouse, she looks like she’s just stepped out of a Helmut Newton photograph, circa 1975. With roots in the fiery city of Naples -and a working life divided between Paris and London- you’d expect her to be this intimidating, modern day glamazon, but there’s a sweetness and warmth to her that makes you feel instantly at ease. As she kindly invites me to sit down next to her on the cozy sofa of her spacious office, I can’t help but notice her transparent blue eyes.

Lucia Pica may be connected to women and a rather humble person, she nevertheless has the gaze of the dreamer and the power of the visionary. Listening to Pica talk about make-up and her love of color is quite inspiring, because

you feel her commitment and involvement all the way.

Overseeing hundreds of products each year is a daunting task — especially when you work for one of the most celebrated houses in the world — but she makes it sound all easy and effortless. Whether she talks about her inspiration trips abroad or the smooth texture of an eye shadow, you want to know more about her process and what really makes her tick. In this exclusive interview, Lucia Pica evokes beauty as the embrace of our imperfections and individuality, how make- up can suddenly alter our mood and why being a voyeur comes naturally to her.

Philippe Pourhashemi: You are Italian,

but moved to London in 1998. Why did you choose England?

Lucia Pica: I was born in Naples, but realized I wanted to leave Italy as it felt quite limited. I also wanted to travel and London seemed so appealing to me at the time.

PP: Did you speak English fluently?

LP: I had learned it at school, but didn’t speak it well. I really learned it by living in London.

PP: How did you perceive Chanel as a little girl growing up in Naples?

LP: Chanel is such an iconic brand that

it feels like it’s always been there. It’s an historical House, too, and I remember being obsessed with the Rouge Noir nail polish I wore in the mid-90s. That color attracted so many women and I was only a teenager then, but all my girlfriends wanted that shade and it turned into this fixation. People had to have a pale face and dark lips.

PP: Sounds quite 90s Goth to me.

LP: A little, yes. I wasn’t so aware of Chanel perfumes back then, it’s definitely through beauty that I got to know the brand. In the first collection I did for the House, I created Rouge Audace, which evoked Rouge Noir with slightly more brownish hues.

PP: Red is one of your signature shades.

LP: Definitely. I like all kinds of reds: they could be a bit purple or darker, as long as they are warm.

PP: How do you choose new colors? That process must be quite consuming.

LP: As I design collections for a brand that epitomizes luxury worldwide, I feel it’s important to have depth when it comes to research and inspirations. Every year, I pick a new destination to travel to, although

I often have no clue what I’ll be finding there. I usually take a photographer

I know well with me and we start looking for details that catch our eye. The fact that I have a close relationship with each photographer means that the pictures will be more personal and close to the themes

I want to develop.

PP: Where did you go for the SS/19 collection?

LP: I went to Tokyo and Seoul with Harley Weir and we stayed for 4 days. The goal was to understand the vibrations and special features of each city, while translating their culture into direct references. For instance, people in Asia pay more attention to detail than we do in Europe, and that dedication and care inspired me. They can take something small and make it extraordinary.

PP: I’ve been to Seoul many times and love its energy.

LP: Actually, I felt that energy, too, and wanted to translate it into certain colors

I picked. Harley and I spent 5 hours at the fish market for instance, taking pictures of scales and all kinds of food, anything we found attractive really. It’s a very spontaneous way to work together and there is no preconceived idea of what we’re going to see.

PP: I love the way you have it printed out in a large format later, sharing your own mood board with others.

LP: Exactly. I like the way Harley takes something quite banal to turn it into something more expressive and dramatic. That kind of elevation inspires me, and her pictures are like paintings to me. I like

to be generous and share them with others, so I’m not really protective when it comes to my inspirations. I present the images to my team, and a picture becomes a reference for an eye shadow or a new lipstick.

PP: Do you know already what colors you’re going to have within the collection?

LP: Sometimes it’s quite clear how an image becomes a product. The fish scales became an eye gloss and also made me want to have more luminous effects on the skin. One of my favorite products within the line is Le Baume Essentiel, a clear glossy stick that doesn’t look like make-up. I like the idea of having products that take care of the skin while enhancing features. I used it for the make-up of the beach-inspired ready-to- wear show presented last October.

PP: Do you always art direct the make-up of the shows?

LP: I started with the last Cruise and SS/19 shows and I’ll continue doing these in the future. The great thing about working for Chanel is that we have a lot of creative freedom and also the ability to change our minds during the elaboration of the collections.

PP: How much in advance do you have to design them?

LP: We have to work a year and a half in advance, which is completely different from the rhythm of the fashion collections. Developing a new product takes a very long time for us and we need to plan everything ahead. Being a woman, I also need to bear in mind that each product must be pleasant and comfortable to wear. Luxury is not only what you see on a face, but how products react to your skin.

PP: Are there any restrictions within Chanel make-up?

LP: There is a framework, and sometimes formulas do not work technically, but we have a lot of space to create and experiment. For me Chanel means quality and elegance, you can do anything as long as you respect those parameters.

PP: What does French elegance evoke

for you?

LP: I like the way French women wear sophisticated clothes. There’s an effortlessness to French women that inspires me. It’s not about being constructed at all and perhaps an Italian woman likes to look more “done”. The same goes for Americans. Still, I find Italians more expressive, whereas English women like being more unconventional.

PP: You’ve once described Gabrielle Chanel as a “punk”. How do you challenge boundaries within your own field?

LP: I’m very rebellious, not for the sake of it, but when I believe in something I will really defend it. I love bold colors because they allow you to express your personality, but I try to create a palette that expresses strength and softness at the same time.

I’d like women to be more playful with make- up and mix different textures to invent something that suits them. I don’t want to direct them too much and make-up should always be a moment of pleasure for women.

PP: How do you know that a color is going to be a hit?

LP: I couldn’t explain it (she laughs). I hope I feel it from within, but it’s completely instinctive for me and I have no idea where it comes from. I also enjoy starting with an idea and changing it completely afterwards. Again, it’s very hard to explain that kind of creative impulse.

PP: Do you observe people around you a lot?

LP: Definitely. My job is to be a voyeur and to look at women, as well as enjoy any kind of cultural expression, such as art, movies or exhibitions. I have a group of friends around me that I find really inspiring, which means I am connected to the reality of women’s lives.

PP: What is ‘bad make-up’ in your opinion?

LP: Bad make-up is erasing yourself to try to look like someone else. I have no interest in make-up rules that are dictated to women, mainly through social media.

PP: How do you define ‘bad taste’?

LP: For me, there is a very thin line between an elegant red and a trashy one. Trashy can be good sometimes, it really depends.

PP: You’re not into pink that much, are you?

LP: No, I like pink, but it’s not a color that I’d wear myself. I created pinks before, because I wanted this Pop Art feeling, but I don’t like girly pink. I prefer confrontational pink.

PP: Having worked here for 4 years now, what is the key difference between Chanel and other houses?

LP: Well, I have never worked as a creative director for other houses before, but Chanel really supports creativity and quality is a leitmotiv. We do carry out extended tests to products in-house that I know other brands won’t do. We really take the time to develop ranges and then you have the Chanel stamp on them, from the look of the packaging to the feel of a texture.

PP: How did you end up working here? Were you “chosen”?

LP: I was actually. I had been doing lots of editorials and was asked to do a beauty campaign after Peter Philips left. I think they were trying out different people to see who would do the campaigns, and eventually I did all of them. At the same time, they were looking for a new creative designer and I had a few interviews before I was offered the position.

PP: You have an impressive portfolio of collaborations with photographers, from established to more avant-garde names.

LP: Yes. It prepared me for the job now, because I was always experimenting with color and texture. Passion helps, obviously. After 4 years, I feel quite settled here even though it all went so fast. I feel quite happy about certain things I have achieved so far and there’s definitely a close understanding with the team here.

PP: Do you still do editorials?

LP: Yes, but a little bit less. I still love doing them.

PP: Is there any photographer you feel specially connected to?

LP: It’s always been nice working with people like Alasdair McLellan, Willy Vanderperre, Mario Testino or Juergen Teller. Some people I almost grew up with, but I have been lucky enough that I’ve worked with people whose aesthetics appealed to me,

so I could really give them something that they liked in return.

PP: Do you feel with social media that make-up tends to become louder and more in your face?

LP: It’s a very fine line. There are so many ‘make-up experts’ now that it becomes confusing at times. There is also this idea of conforming to certain trends, which I’m really not crazy about. I like to see individuality around me and on Instagram there’s this make-up overload going on. It has gone too far, especially when I look at posts of women with crazy contoured marks, almost tattooing their eyebrows. They look pretty scary.

PP: As a Frenchman, Chanel symbolizes for me a certain bourgeois taste that relies on very specific codes. How do you see that?

LP: There is this kind of bourgeois and opulent dimension, but there are also daring and courageous elements within that. Rouge Noir was for instance a really daring statement and that’s really out of the box.

PP: Would you like to design iconic products like Rouge Noir? Is that a dream of yours?

LP: Definitely (she laughs). I wish I’d done it. The red eye shadow palette I did within my first collection reached out to quite a lot of women and that’s been a successful and trend-setting kind of product.

I remember seeing people on the street wearing red eye make-up at the time quite easily and I wondered if it had anything to do with that.

PP: Do people sometimes approach you telling you how the make-up you created affected them in a positive way?

LP: Sometimes, yes. If you try new products on people, they can get quite fascinated with them.

PP: Is make-up empowering for women?

LP: Definitely. I see make-up as one of those tools for women to easily fix something and alter their moods. Keira Knightley once told me that she puts red lipstick on when she feels a bit down and even Mademoiselle Chanel told women to put their lipstick on and attack, like an armor in a way.

PP: Do you have a routine for your own make-up?

LP: I use lipstick, La Palette and Les Baumes every day, as well as matte eye shadow and mascara. I don’t try all the products on myself though.

PP: I really like what you’re wearing.

LP: It’s Chanel.

PP: Of course it is. Which pieces do you usually pick?

LP: I tend to go towards the more tailored garments. I like the 1960s and 1970s mixed with the 1990s so it ends up looking a bit retro on me. I also love wearing mini skirts or dresses with fitted jackets. I quite like to wear Chanel head-to-toe. Maybe I’d wear this suit with trainers.

PP: Do you still feel like an Italian in London?

LP: My English friends always tell me I’m very Italian.

PP: Do you go back and forth between Paris and London?

LP: Yes, my home is in London, but I have an apartment here, in the Saint-Germain- des-Pres neighborhood. I actually love the contrast between the two cities. I’m enjoying Paris quite a lot, because it’s easy to walk around and it’s so beautiful. London is more hectic and it’s hard to do these things. London feels more abrupt than Paris to me, and there’s a charm here you don’t find anywhere else. Paris lies exactly between London and where I come from culturally, quite a nice compromise.

PP: Are you learning French?

LP: I am trying to learn it. I do understand a lot, but I use English for work, especially here. In a way I can separate my work language from my mother tongue, which is a useful thing for me.

PP: There’s a tradition of foreigners working for the House, such as Heidi Moravetz or Peter Philips. Karl Lagerfeld is German, too, although he has lived in Paris for several decades. Do you think this outsider point of view is more interesting?

LP: I guess so, but Chanel style is not exclusively French. Of course, there is a certain Frenchness at play, but I see more of a Chanel idea with a woman who is international, both sophisticated and strong.

Archive from our Issue 6 SS19

…

Interview by Philippe Pourhashemi

Lucia Pica’s portrait courtesy of Chanel

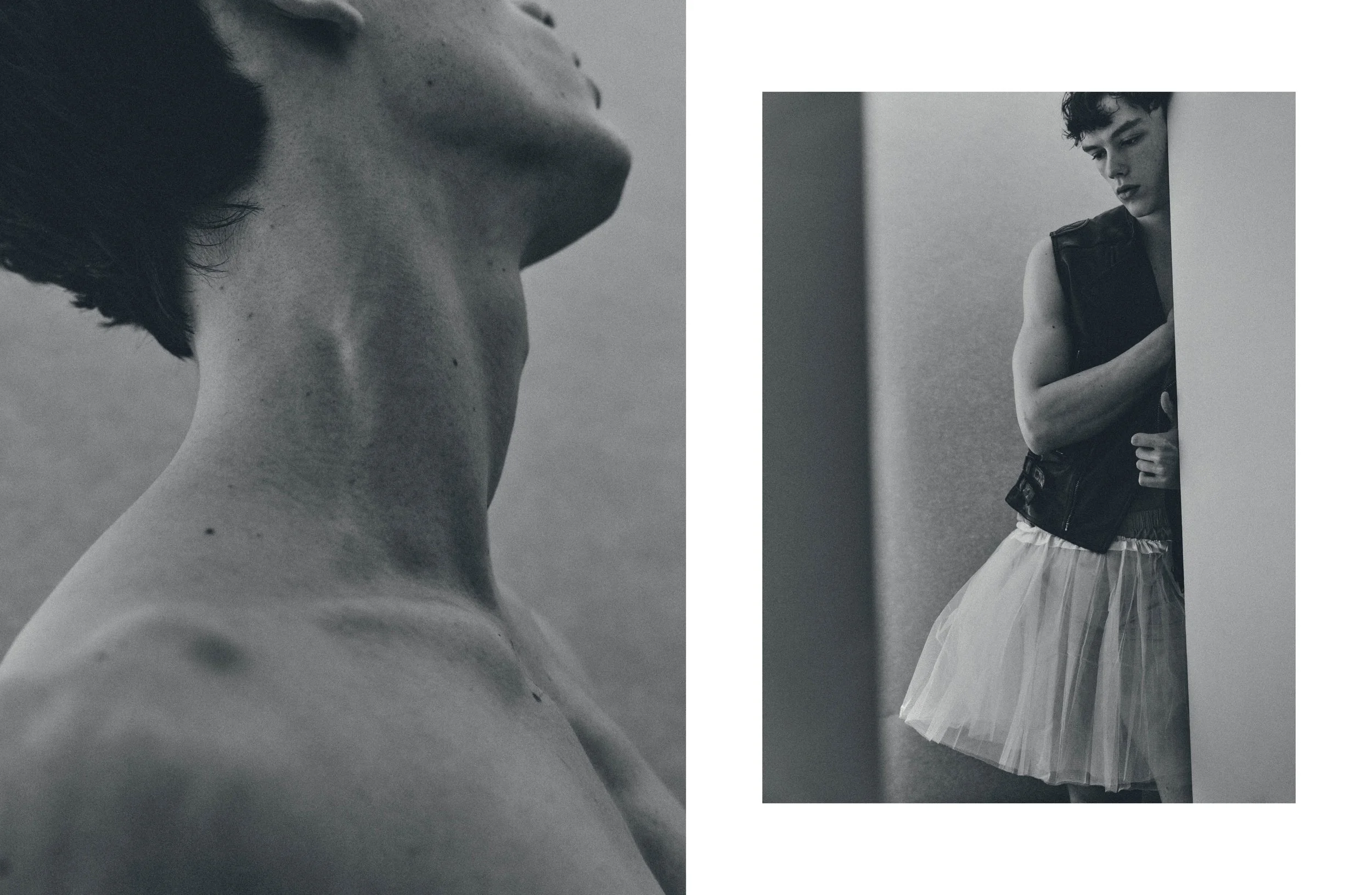

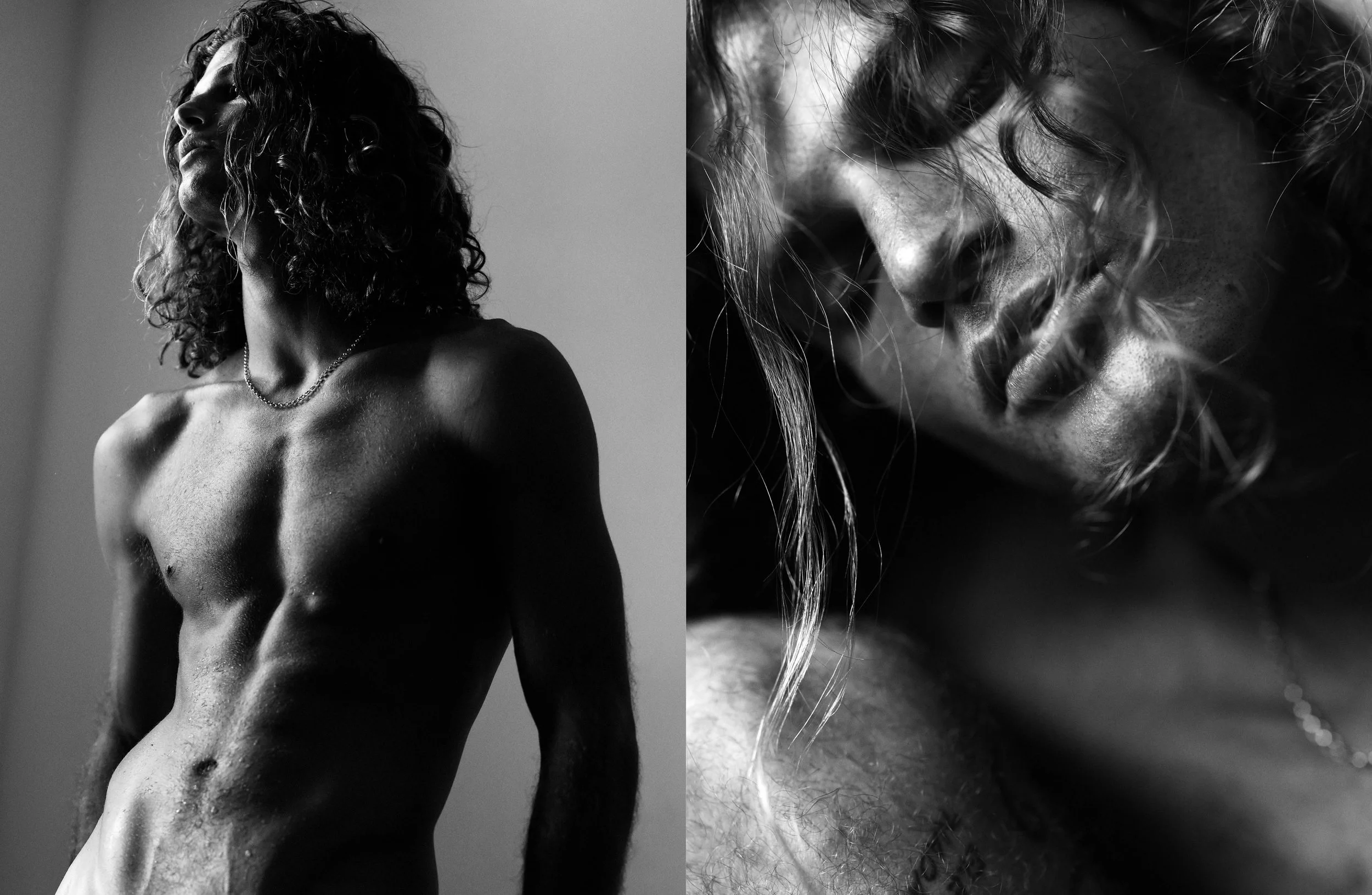

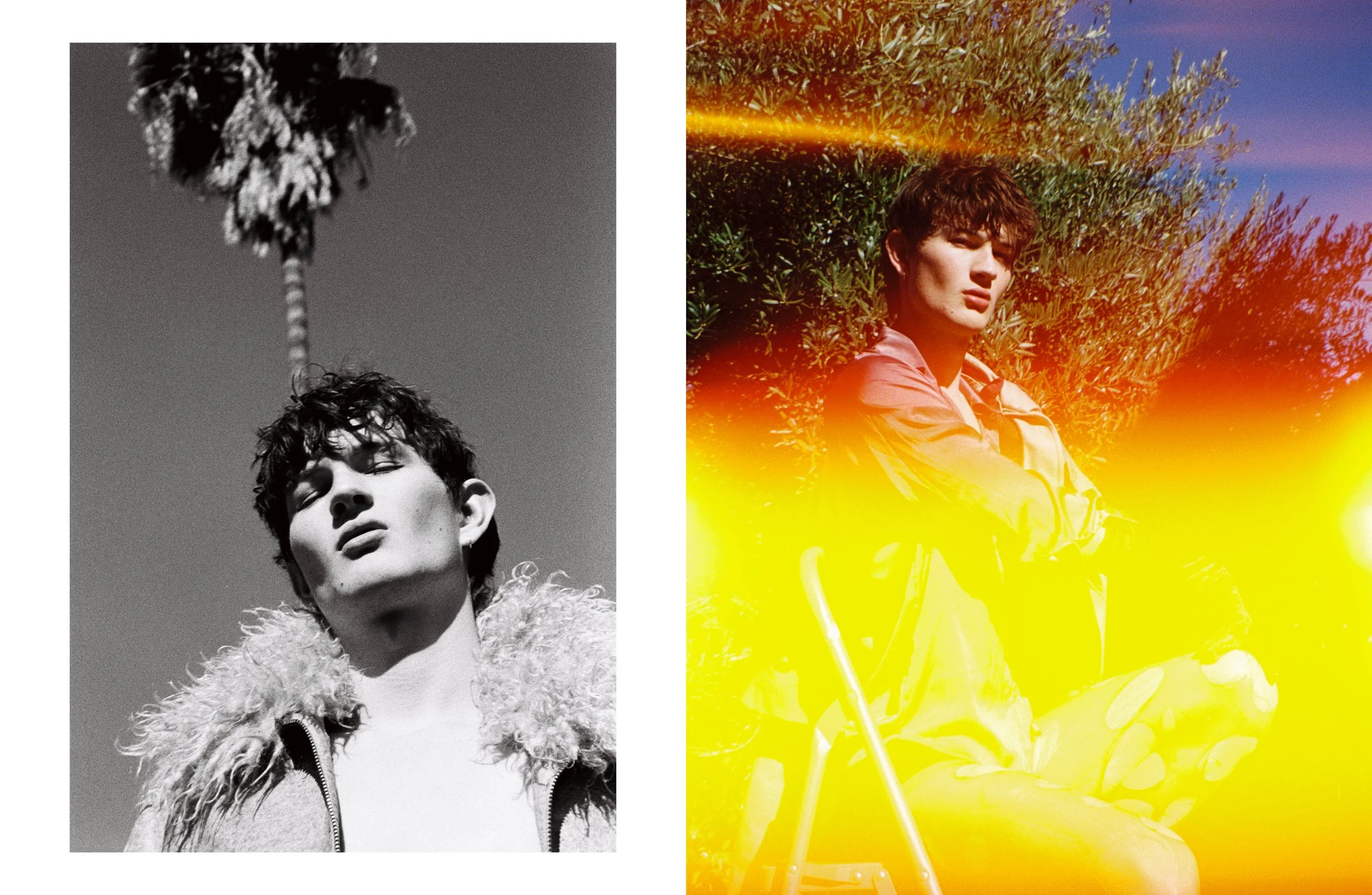

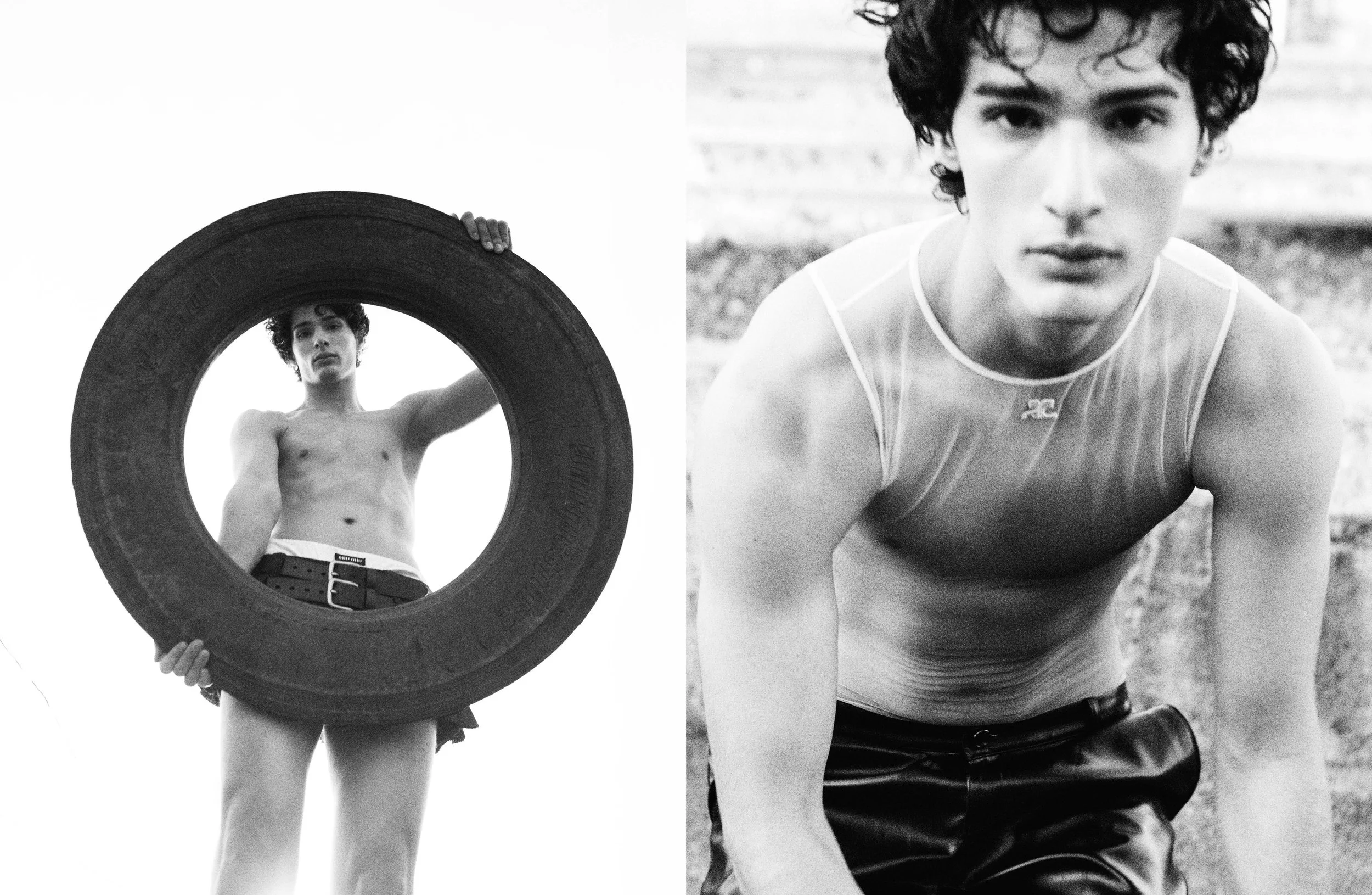

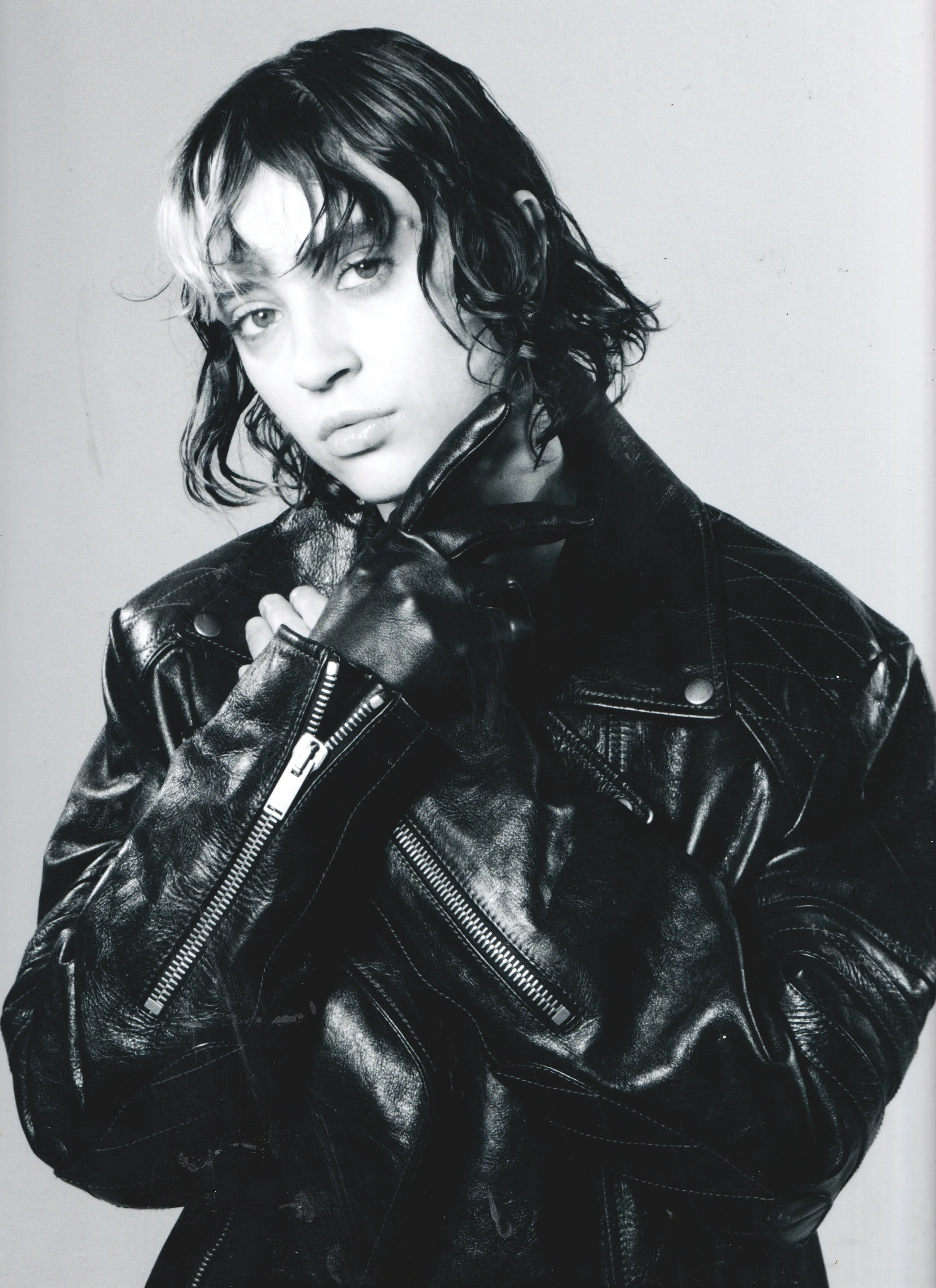

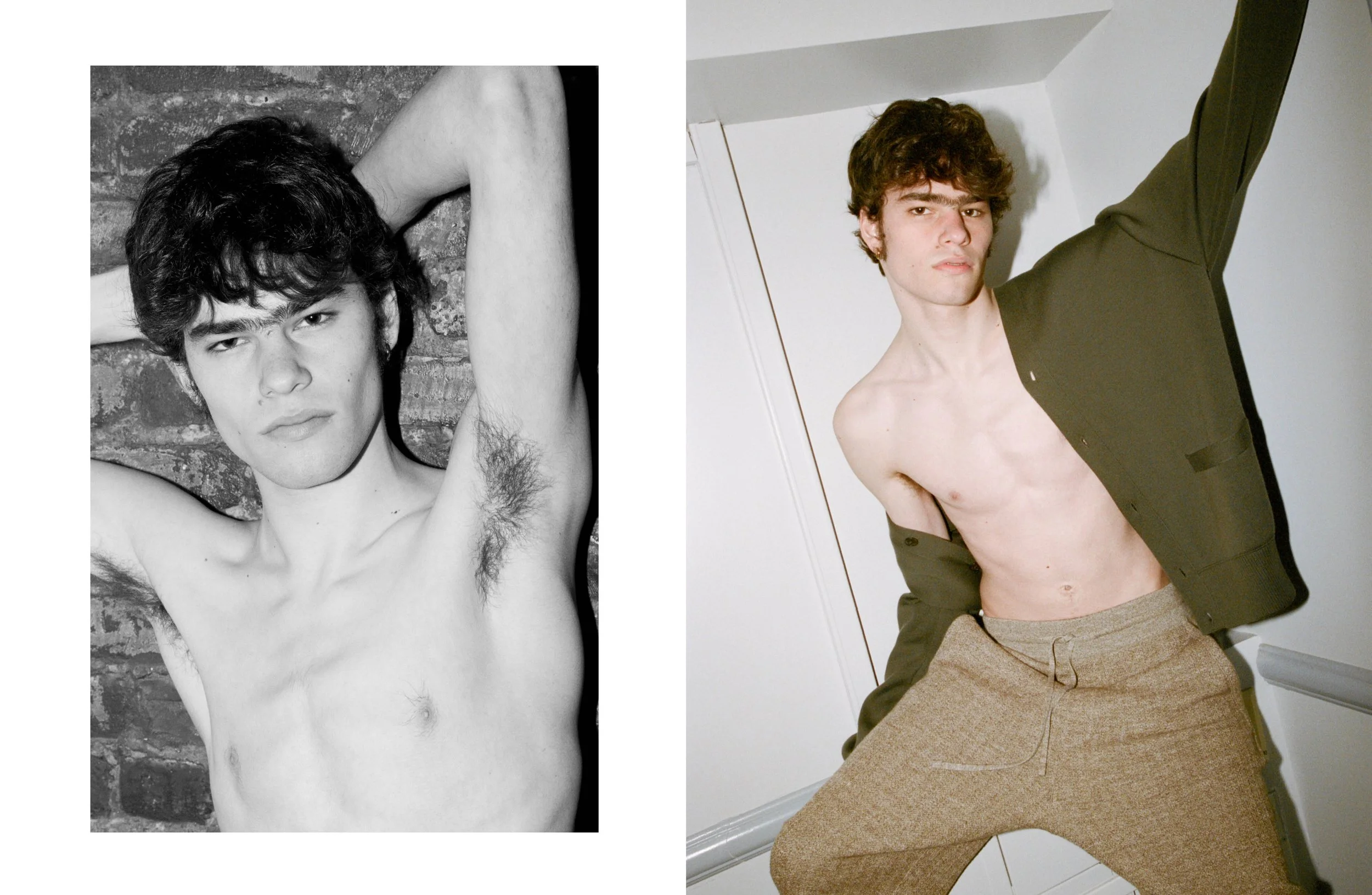

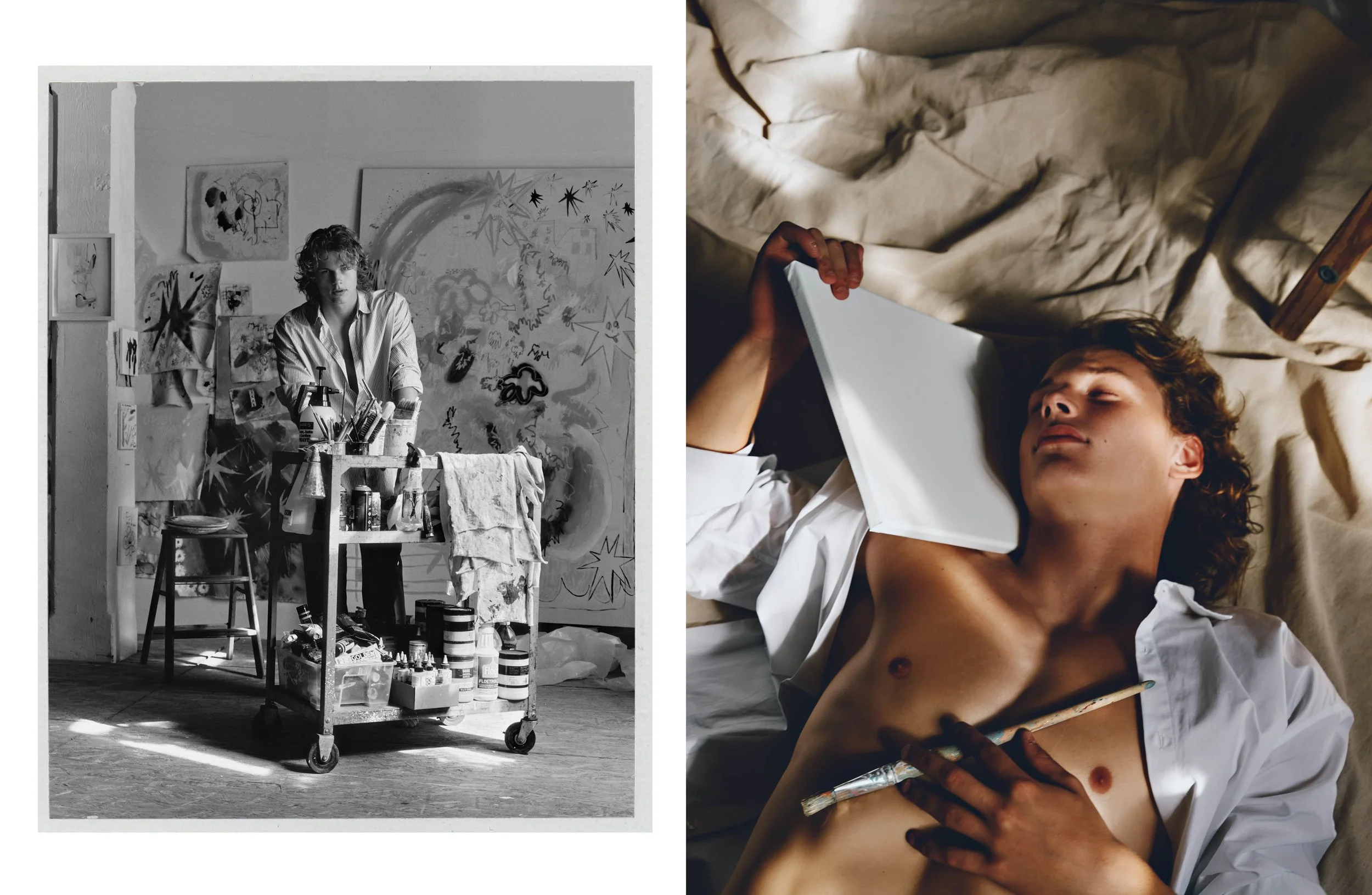

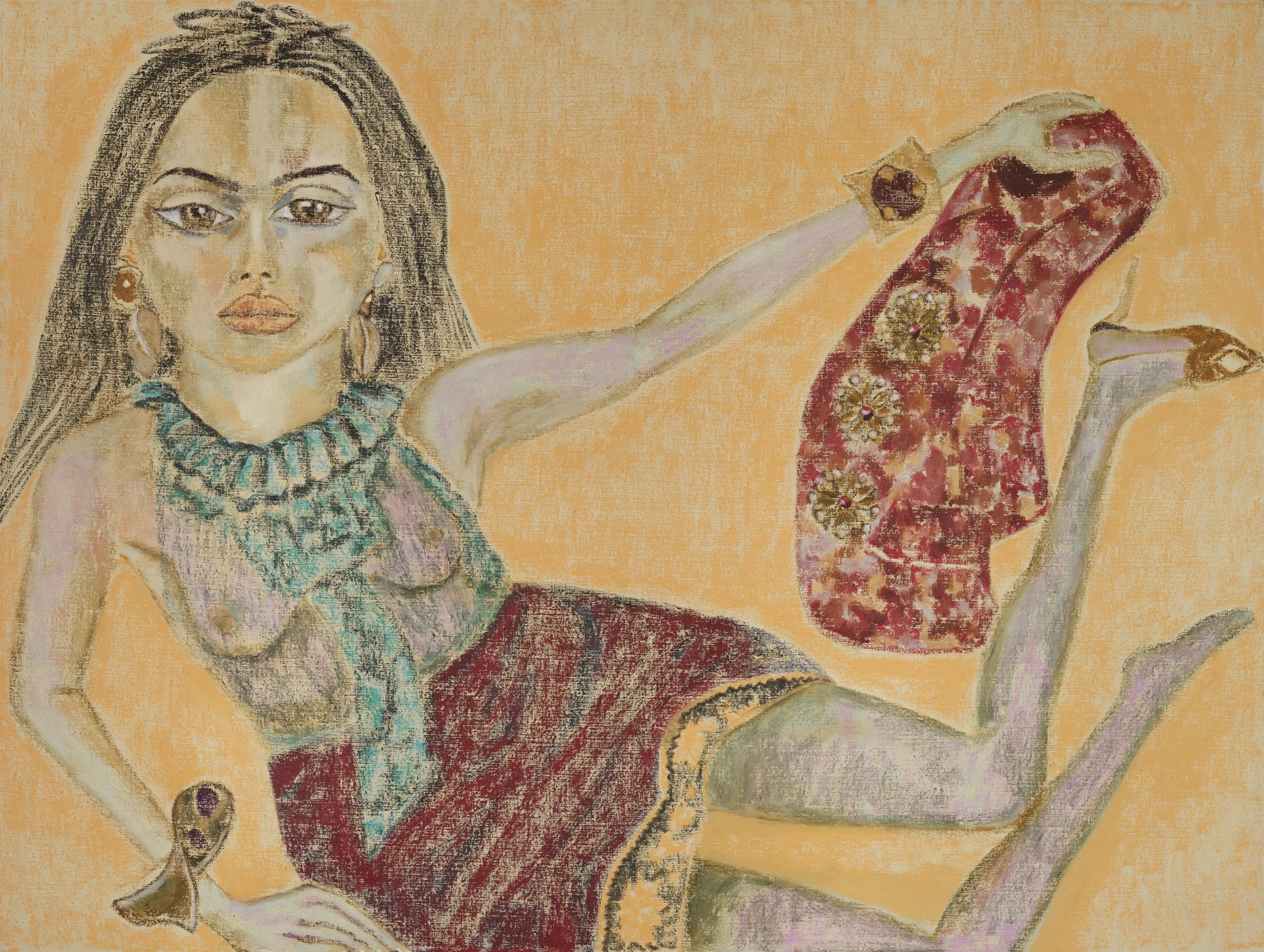

Photography by Martina Bjorn

Featuring Sara Dijkink at Women Management

Make-Up by Sofie Van Bouwel for Chanel at Touch by Dominique Models

Set design by Christo Nogues

Casting by Mitch Macken at MM Casting

Production by Michael Marson

Photographer’s assistant Louis Philippe Beauduin

Production’s assistant Thomas Cleda

Special thanks to Initials LA

![MiuMiuTales&Tellers_#14_ (THE [END) OF HISTORY ILLUSION]_HOST.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/553417b2e4b03cb74b7dfb0f/f714434e-20b1-4f9e-bd9f-4726f54f8e22/MiuMiuTales%26Tellers_%2314_+%28THE+%5BEND%29+OF+HISTORY+ILLUSION%5D_HOST.jpg)