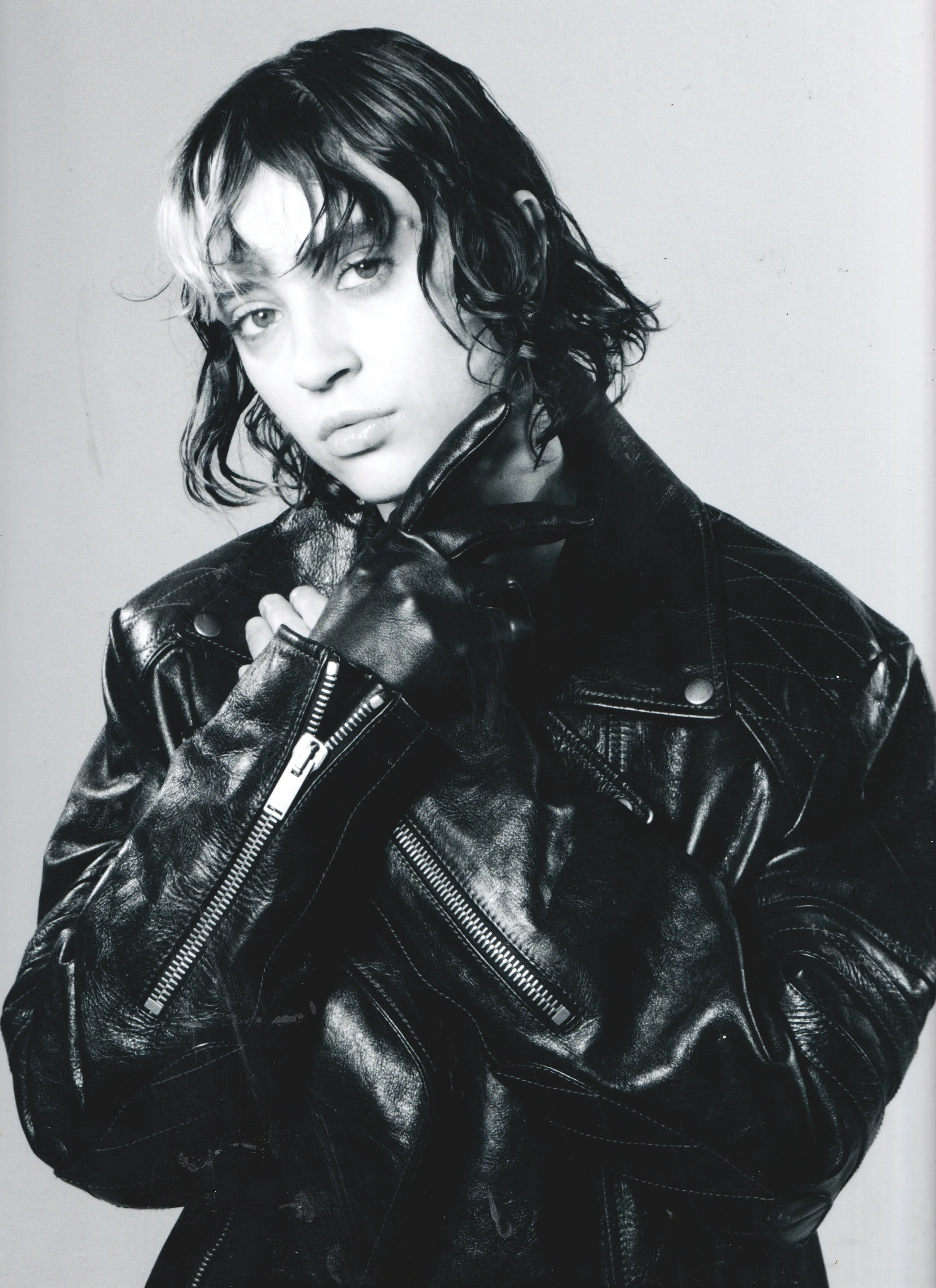

An intimate talk with Isabelle Huppert

Paris, June 2018

Few actors manage to wow critics and audiences alike, owning the screen -or the stage- with their incredible presence.

Throughout her stellar career, Isabelle Huppert has embodied complex, ambivalent and intriguing women, pushing herself to the limit with every new role. Her love of risk and fearlessness when choosing roles is legendary, going where only a few would dare to go.

It seems that Huppert wants to fully explore the psyche of the characters she plays, with authenticity, flair and clinical precision. Often referred to as a “cerebral” actress, Huppert approaches the art of filmmaking through all its facets, describing cinema as a uniquely rewarding and existential experience.

She speaks fondly of directors, costumes, scripts and previous parts, which are very much alive in her mind. This willingness to go all the way and lose herself in her performances still amazes viewers, wondering where she’s going to go next.

Huppert answers questions fast and in a straightforward way, but she sometimes contradicts herself, going back to her original train of thought and adding new elements. In many ways, she refuses to be pinned down or defined as a woman, and she appears fiercely protective.

Despite being known and loved internationally as an actress, the woman remains a mystery figure. In this exclusive interview, she discusses her relationship to the fashion world, posing for famous photographers, Alfred Hitchcock’s thoughts on films and why she doesn’t see herself as a passionate actress.

Philippe Pourhashemi: How would you describe your relation to fashion?

Isabelle Huppert: I’d say it’s a good one. I’m interested in fashion and clothes. Actually, it’s more entertaining for me than an actual interest. I see fashion as something pleasurable. When you see clothes in a show, it’s not something you’d necessarily wear yourself, but they give away hints about the Zeitgeist. You don’t understand why there are certain trends that you see from one designer to another, but fashion tells the story of our times. And I think there is a lot of creativity and invention within fashion.

PP: When you play a part, how do you approach the wardrobe of a character?

IH: It has nothing to do with fashion in this case, but it’s always the first clue you give to the viewer. Costume is essential and nothing is innocent when it comes to the garments you see on screen. Clothes allow you to say something relevant about the character, either in a subtle or more blatant way.

PP: Do you find yourself creating a look for that character?

IH: Yes, of course. I normally work on this with the costume designer and there are directors who are more or less involved in that process.

PP: If we take The Piano Teacher for instance, your character has a very specific style. Did you construct it with Michael Haneke?

IH: No, I worked with Annette Beaufays, who is an amazing Austrian costume designer. In Italy and in Germany, there are also very talented ones, who really understand what it takes to create a character. In The Piano Teacher, there was austerity, and we also had to think about her walk. Would she wear flats or heels?

It ended up being flats for her as she was walking all the time and had to be fast.

PP: At the same time, there were key pieces in the movie, such as her cotton trench- coat, printed silk scarf or dowdy ecru blouse. When approaching such a complex part, what is your process as an actress?

IH: I don’t think you can dissociate this from the encounter you have with the director. In that case, it was Michael Haneke, who is an accomplished filmmaker. I trusted him. I didn’t have any preconceived notions about the part and no expectations either.

PP: What attracted you to her?

IH: Being able to work with him was the trigger. He had already directed a few films that felt significant, and that was the main motivation for me. What I also liked about her was that she was an aggressive, yet terribly vulnerable woman. That kind of contradiction is what you try to bring to the fore.

PP: Do you like these tortured characters?

IH: Yes, because they are major characters. They are exaggerated figures – and you couldn’t necessarily relate them to real life – but such characters deal with central themes, such as desire, sexuality, family and feelings. There’s endless richness in that sense.

PP: Bertolt Brecht applied the “Verfremdungseffekt” to theater, also known as distancing effect. We watch characters, but do not identify or sympathize with them. Would you say this applies to some of your films?

IH: Yes, but it’s not always as clear cut as that.

PP: In Elle for instance, the character you play is not warm or likable. You don’t really want to identify with her.

IH: I disagree. I think you can identify with her and what she’s going through. If we’re talking about Brecht’s distancing effect here, I understand it more as the necessary space you need to create in order to let the viewer make up his or her own mind about the movie. You don’t want to trap the audience with emotion and confuse their reading of the story. I think the distance creates a form of realism that takes us away from more traditional fiction.

PP: At the same time, there’s an uncomfortable feeling in several of your films. I remember watching The Piano Teacher the first time and feeling suffocated by it until your character stabs herself, which acted as a release.

IH: No one ever said that life was comfortable.

PP: But you like that notion of discomfort, don’t you?

IH: It’s not that I like or dislike it, but I accept it as being part of the truth of life.

PP: This issue also profiles designer Marine Serre, who told me she loved the way you wore her clothes.

IH: Yes, I wore quite a few of her pieces for a feature in Dazed and really liked them. I’m not that familiar with young designers though, but her clothes are great.

PP: You’re also known for working with young directors.

IH: Yes, I am quite open that way and have no prejudices.

PP: How did the shoot go for this issue?

IH: It went quite well. The photographer was talented and I enjoyed myself.

Shooting a film is a long and emotional process, whereas posing for a photographer is a short-term experience, even if the shoot spreads over several days.

IH.

PP: What’s the difference between posing for a photographer and shooting a film? You seem to enjoy both.

IH: You cannot compare them at all as they have nothing to do with each other. Shooting a film is a long and emotional process, whereas posing for a photographer is a short-term experience, even if the shoot spreads over several days. I like working with photographers though and was lucky to pose for some of the greatest names, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Helmut Newton or Peter Lindbergh. These are amazing encounters with artists who managed to create their own world and vision within the narrow codes of fashion photography. Photographers like Newton or Lindbergh challenged its boundaries to create something original.

PP: How do you act during a fashion shoot? Do you spontaneously offer something

to the photographer or are you mainly directed?

IH: It’s a bit of both. You’re not really aware of what you’re doing. It’s more about how you feel: are you comfortable or not, is it pleasurable or not? Then you check the images and decide for yourself. The result is what matters.

PP: Did you also get that pleasure from every film you have made until now?

IH: Yes, I have. It’s better that way.

PP: It’s hard to keep track of all the films you’re in.

IH: I did play in many, and I intend to continue in the future.

PP: What would you do if you were not an actress?

IH: I have no idea, but I am sure I’d be able to move on somehow.

PP: Talking about truth and authenticity, is what you bring in a film as genuine

as reality itself ?

IH: It’s not as true as reality is, because it’s a movie. It is elaboration first of all, a metaphor of life. A film is not a documentary, but a work of fiction, which extrapolates on reality and the notion of truth. Even a photograph, which may seem more accurate or reliable, is a representation of what reality is.

Cinema is constant

re-creation

; you say words that you never used before and enter bodies that were previously unknown.

IH.

PP: With your experience, does the way you use your body in front of the camera become second nature?

IH: It’s always been that way for me. Cinema by definition is unprecedented, recreating that first time experience with every new scene. I see it as an existential ride, especially when you’re confronted with people you’ve never met or worked with before. Cinema is constant re-creation; you say words that you never used before and enter bodies that were previously unknown. It’s unexpected, every single time.

PP: Do you watch yourself on screen?

IH: Less than before. At the beginning of my career, I’d watch the dailies every day. I don’t look at myself on screen that much, except when the film is over of course.

PP: Are you your worst critic?

IH: I do measure my performances, but the moments I like less are not necessarily related to my acting. A film has a life of its own; you’re not the only element as an actor, but part of a larger process. You have to watch it as a whole.

PP: And how do you know you can trust a director?

IH: Pure intuition. That’s one of the gifts you get from life. Of course, it’s not the same if you already know the director and his or her work, but in the case of a first film, it’s just instincts. And a good script. Cinema is always a collective effort.

PP: Do you intervene on the script itself ?

IH: Yes, it happens. You can always make it better or more accurate. If you realize most of the script has to be reworked, then it’s better not to go there.

PP: The theme of our issue is “Borderline” and many of your parts embody that notion, particularly Paul Verhoeven’s Elle. Why is ambiguity so interesting?

IH: I’ve been reading some of Alfred Hitchcock’s texts lately and he talks about how films should create jolts in the audience and I like that notion. This relates to Paul Verhoeven’s films as well. The viewer goes to the movies for this, and cinema brings that aspect, too.

PP: Are you a committed and passionate actress?

IH: These two words do not resonate with me. Committed? In my own way.

PP: And passionate?

IH: Let’s just say that I like what I do. Let’s even say that I love it!

Archive from our Issue 5 FW18

…

Interview by Philippe Pourhashemi

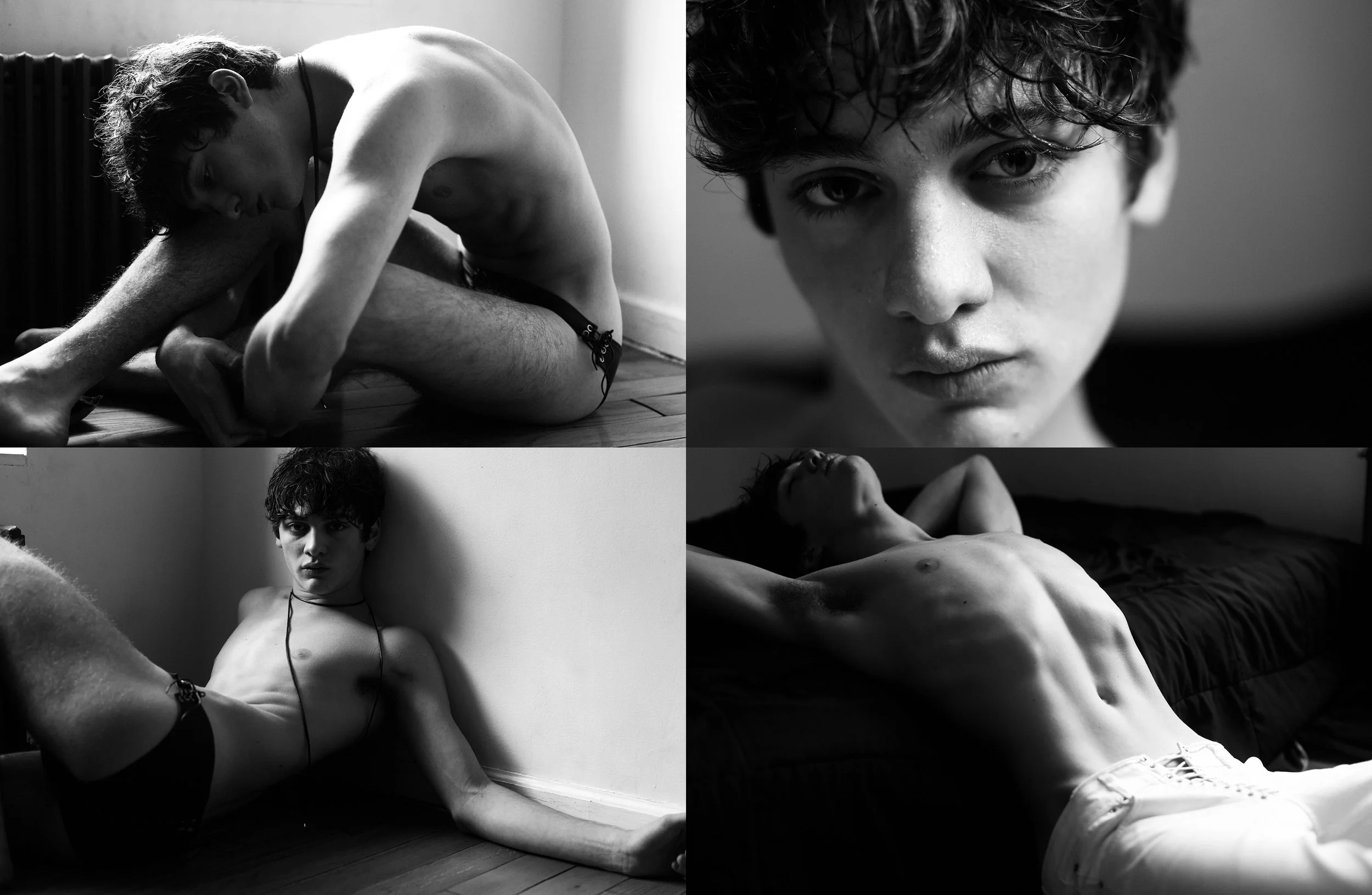

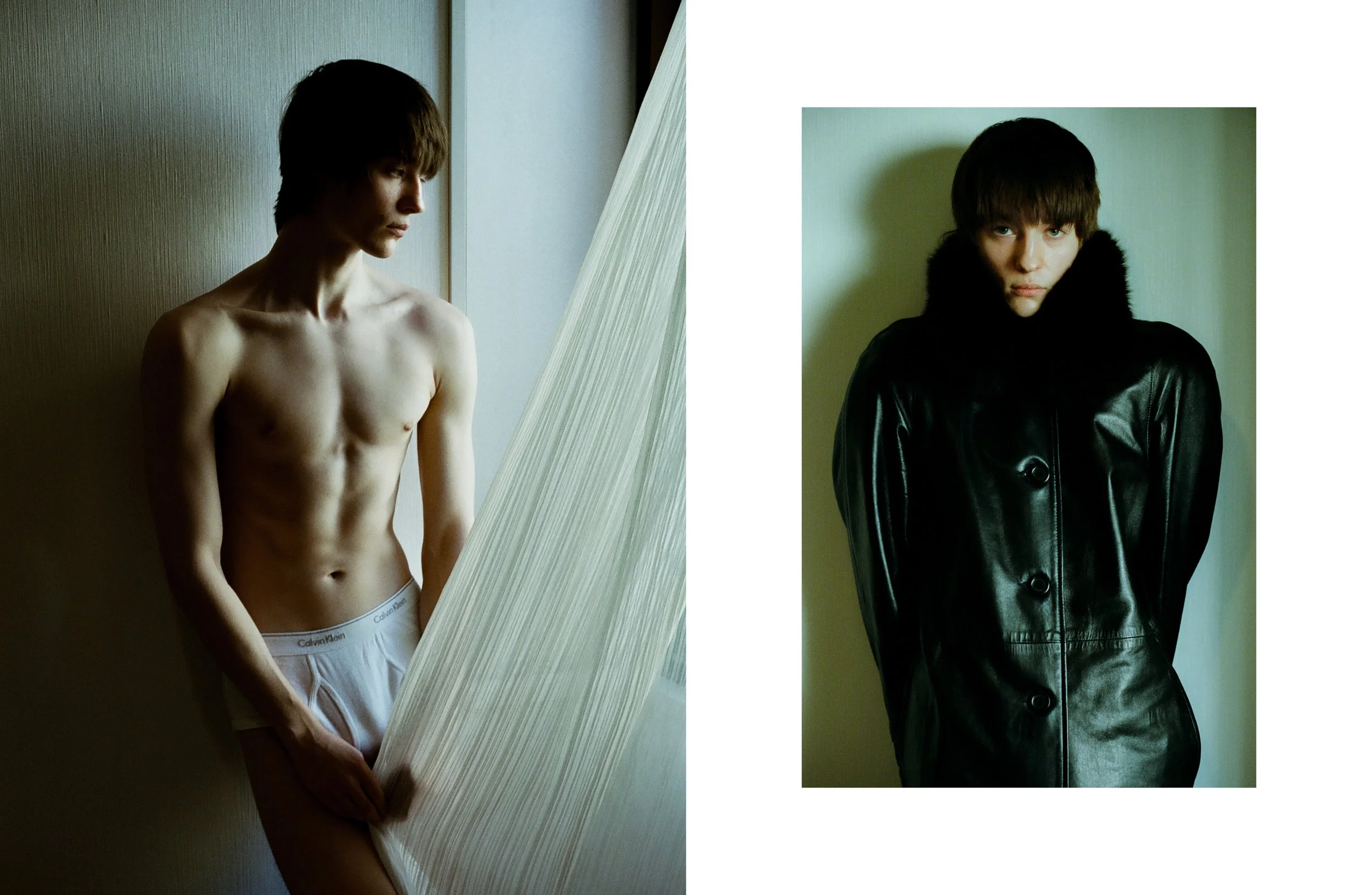

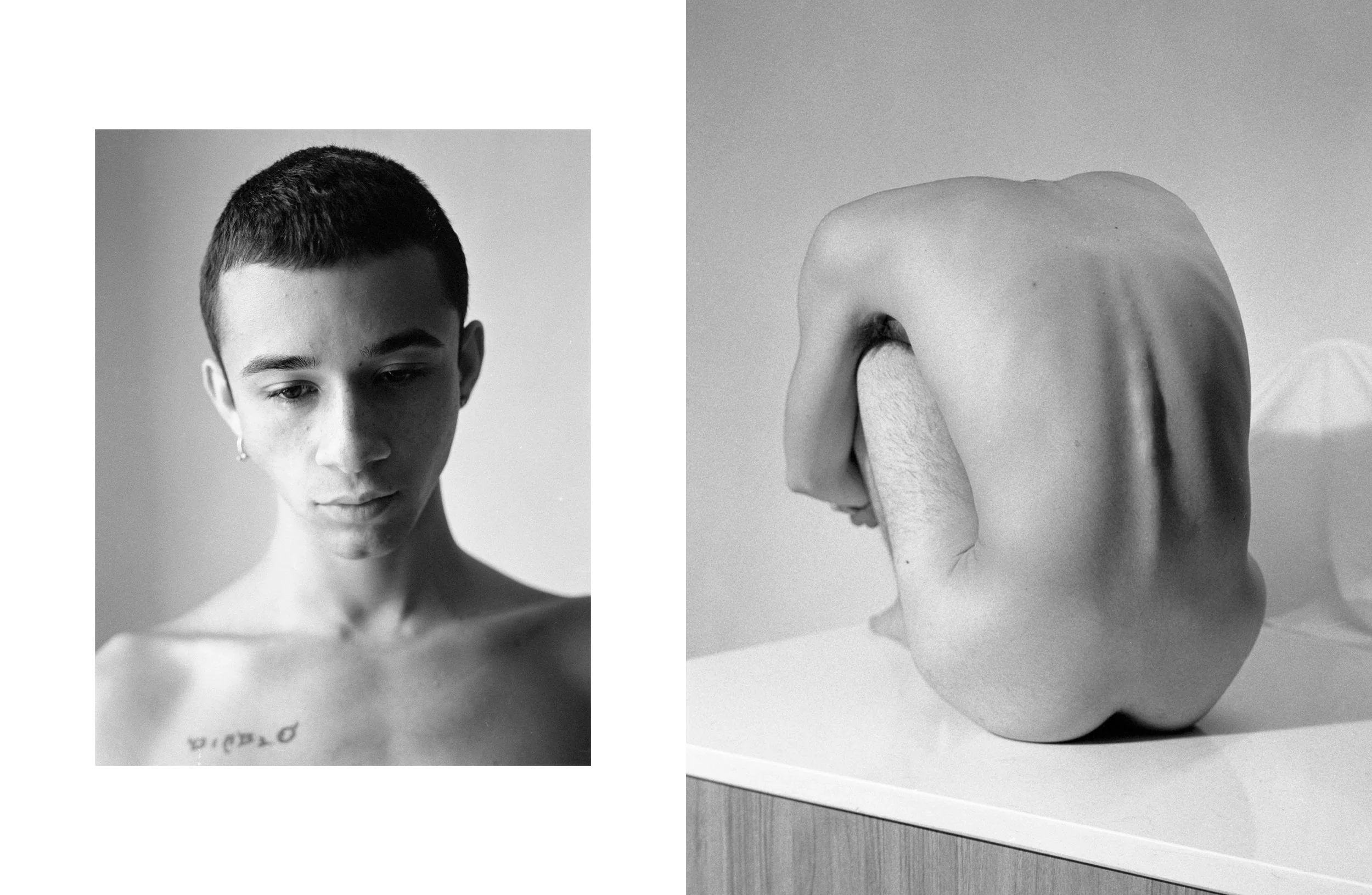

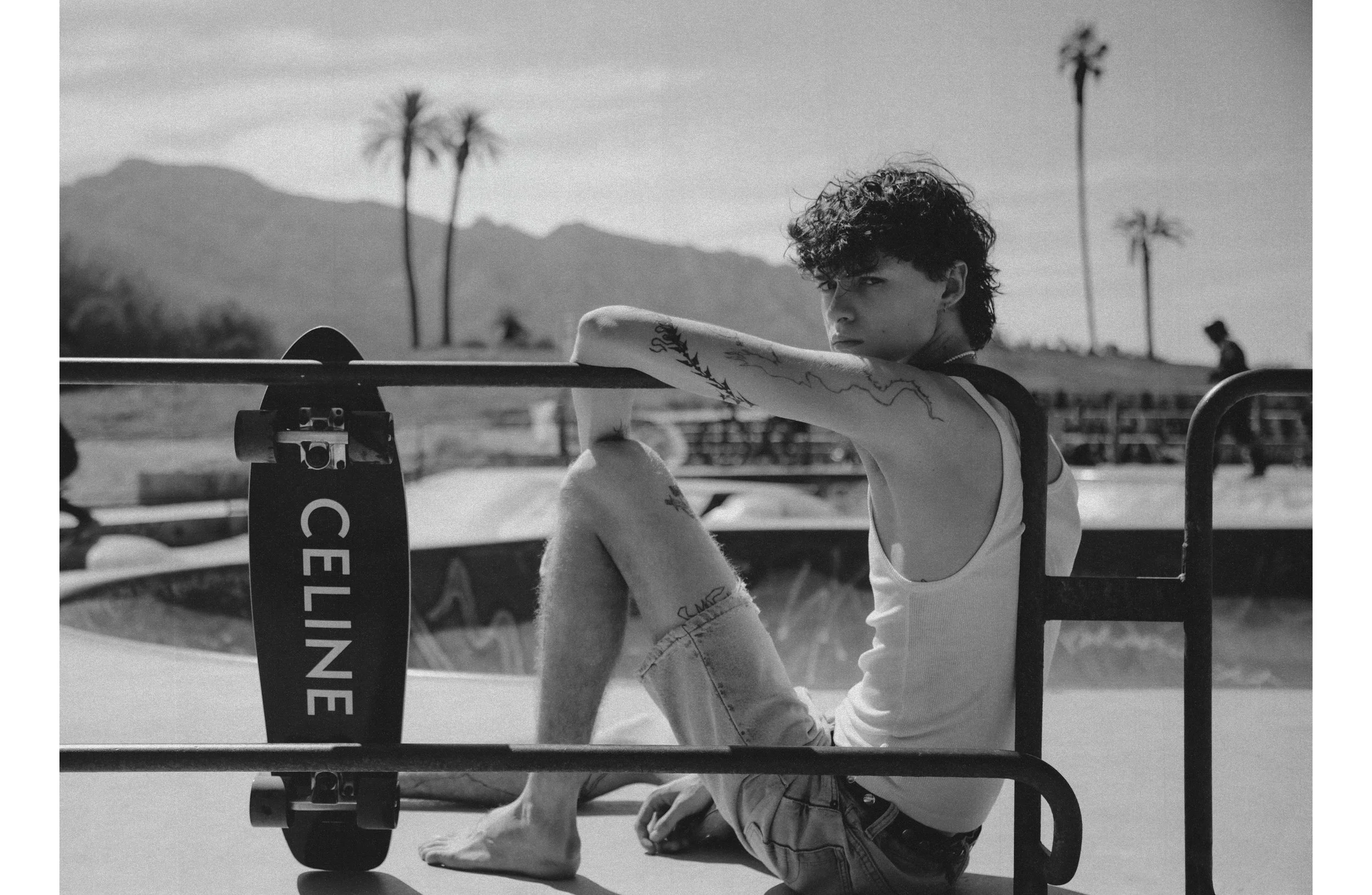

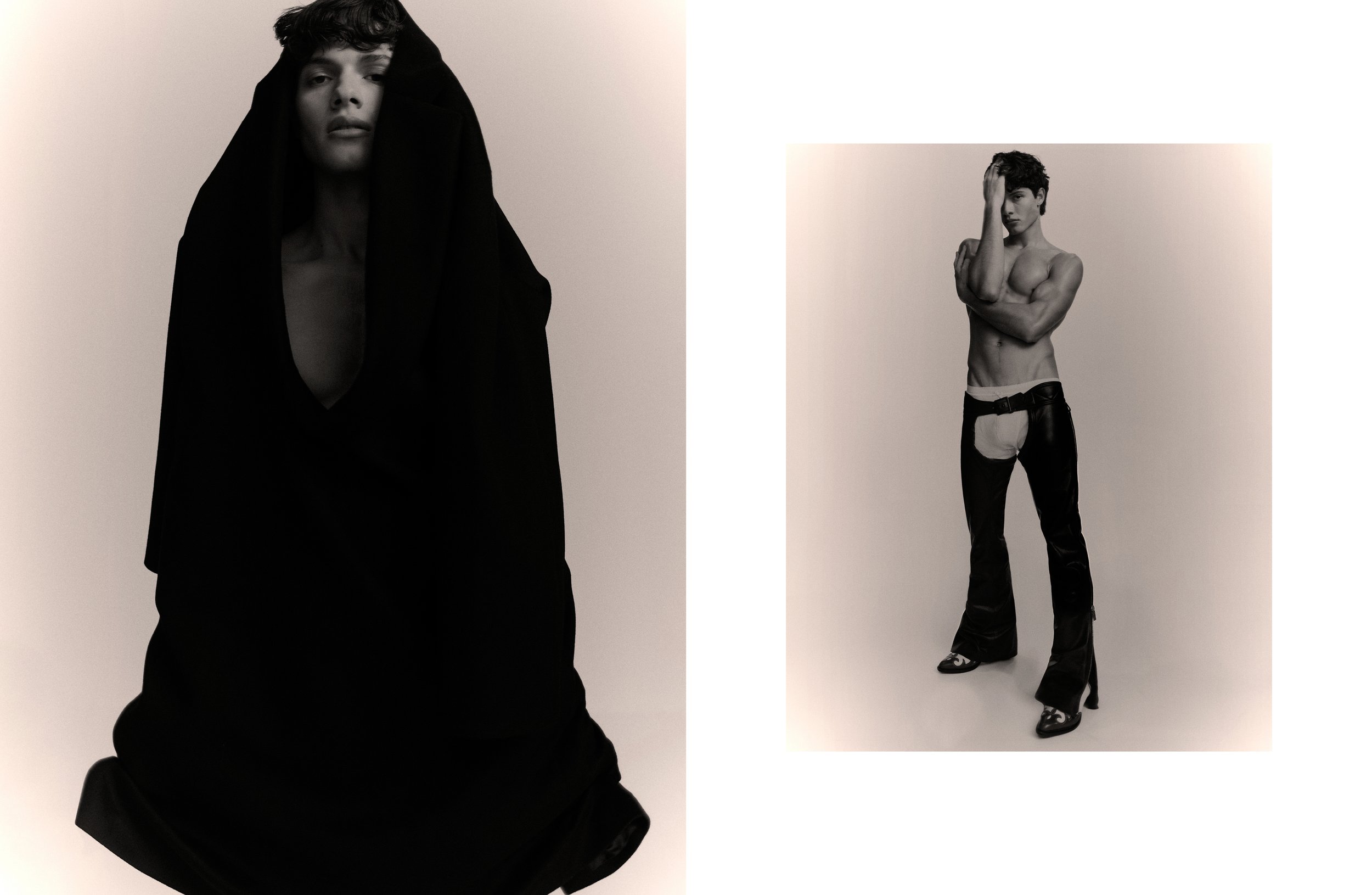

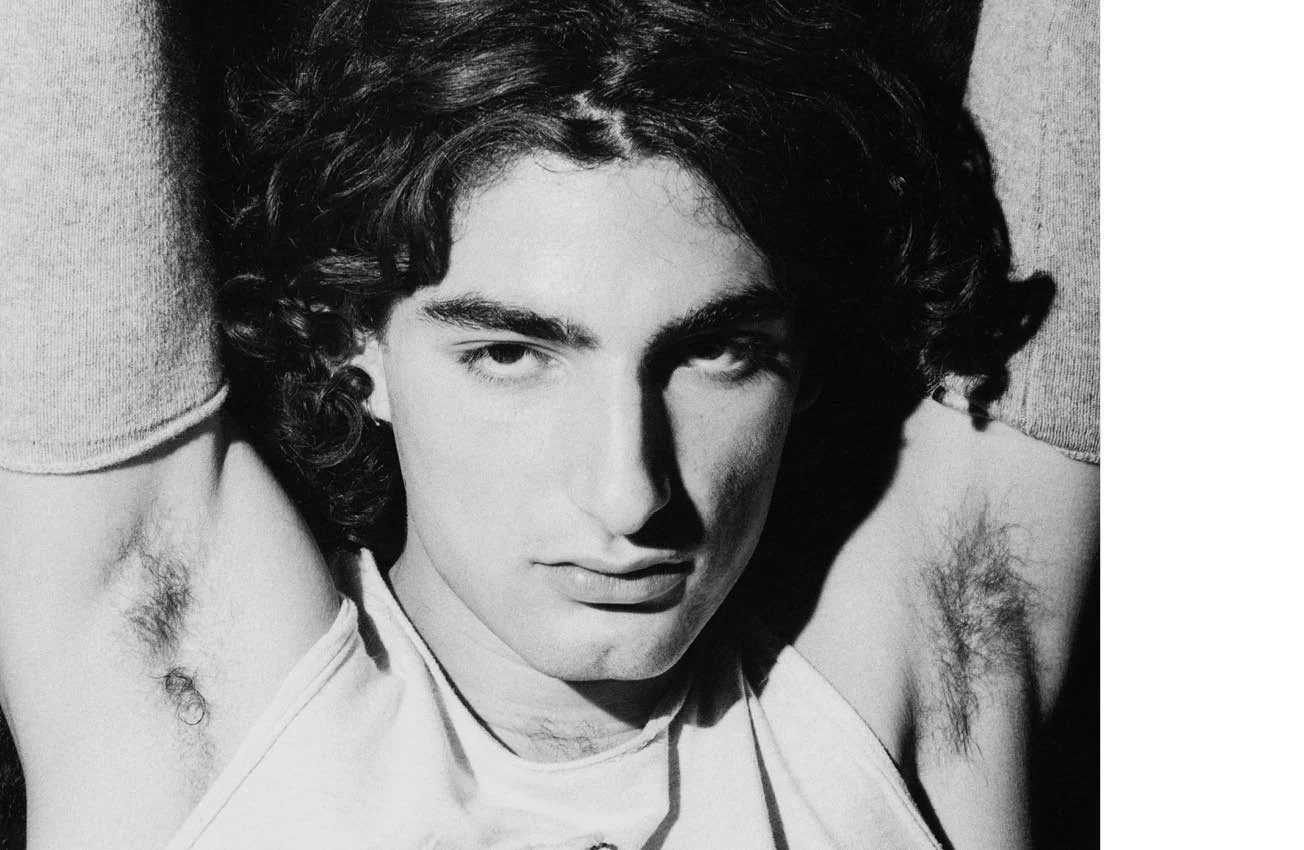

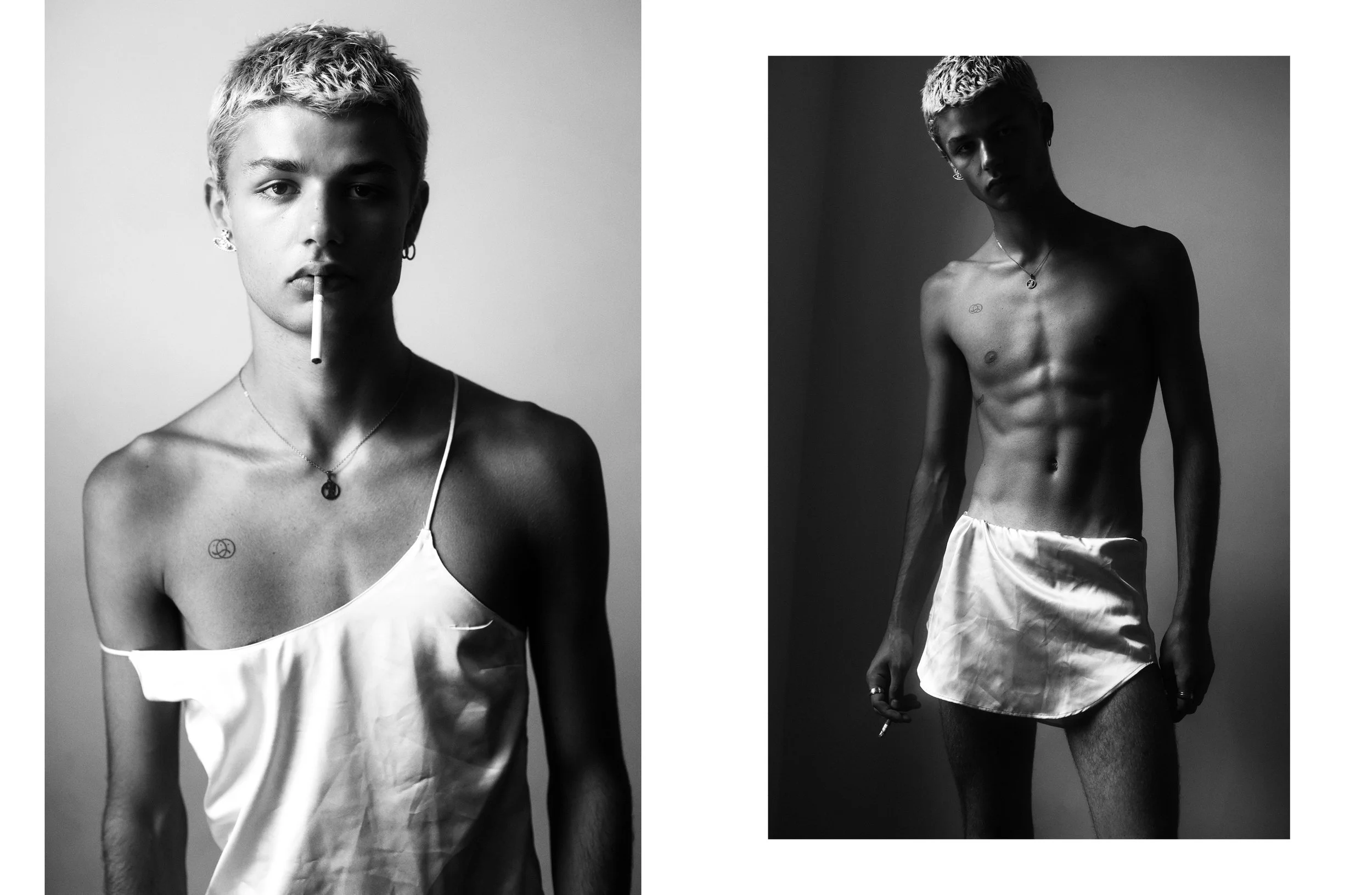

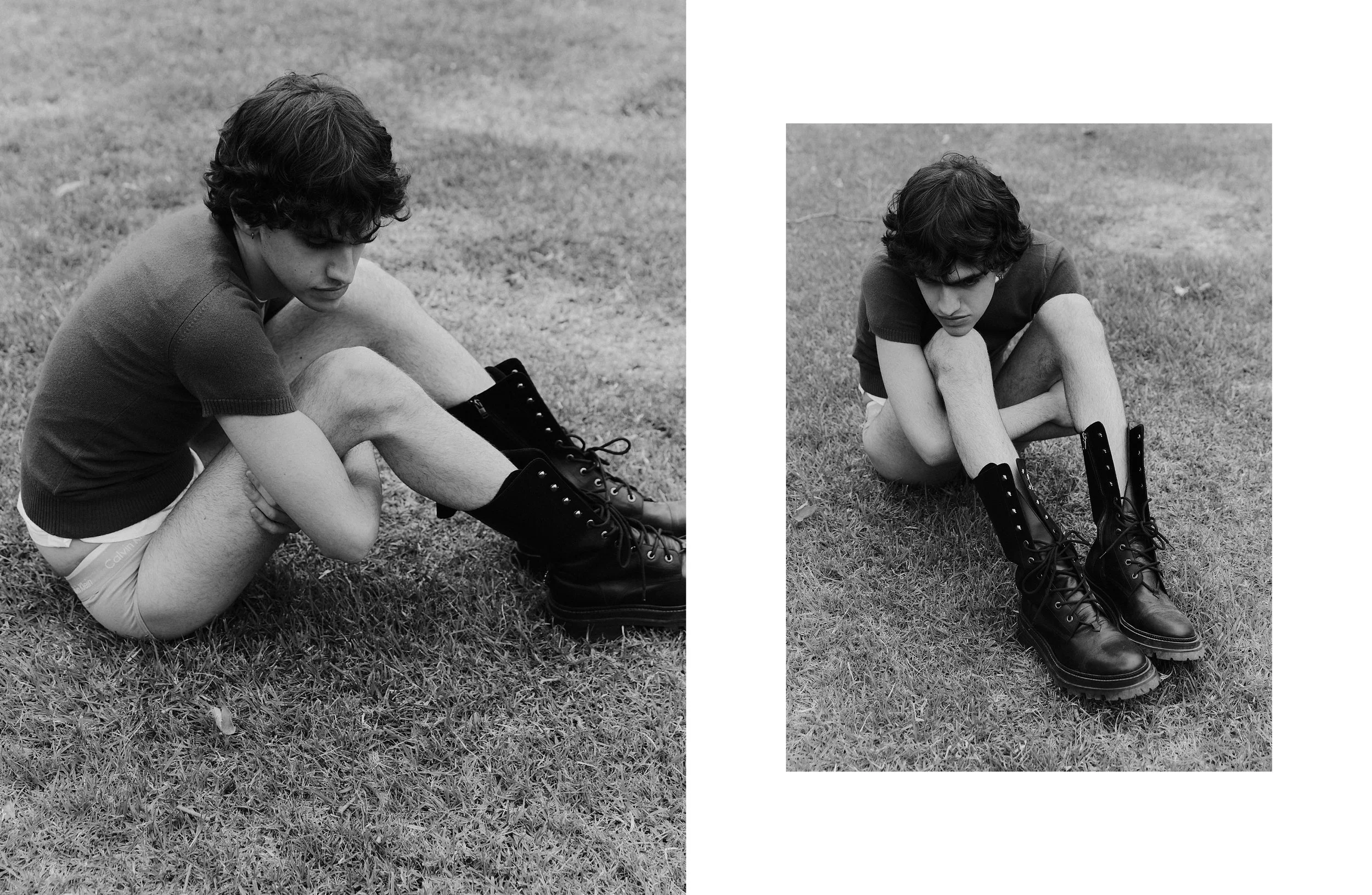

Photography by Łukasz Pukowiec

Fashion by Jonathan Huguet

Hair by Alexandry Costa at Artlist

Make-Up by Anthony Preel at Artlist

Production and casting by Anna Rybus with Prospero Production

Set design by Christian Feltham

Retouching by Paul Drozdowski

Stylist’s assistants Marie Soares and Léa Mai Ngo Hong

Jonathan Huguet is represented by Artlist

…