SOME JOURNEYS ARE PLOTTED ON MAPS, OTHERS TRACE INVISIBLE LINES BETWEEN MEMORY AND CREATION. FOR ARTIST DAVID HOLZAPFEL, A SUMMER TRIP WITH PHOTOGRAPHER HADAR PITCHON WAS BOTH – FROM SUN-WASHED GREEK ISLANDS TO THE SILENT WEIGHT OF VISITING THE AUSCHWITZ DEATH CAMP MEMORIAL. IN BETWEEN, THERE WERE ENDLESS HOURS OF CONVERSATION, IMAGES CAPTURED AFTER FATIGUE STRIPPED AWAY PERFORMANCE, AND A PINK-WALLED REFUGE WHERE MORNINGS BEGAN WITH FRUIT PICKED STRAIGHT FROM THE TREE.

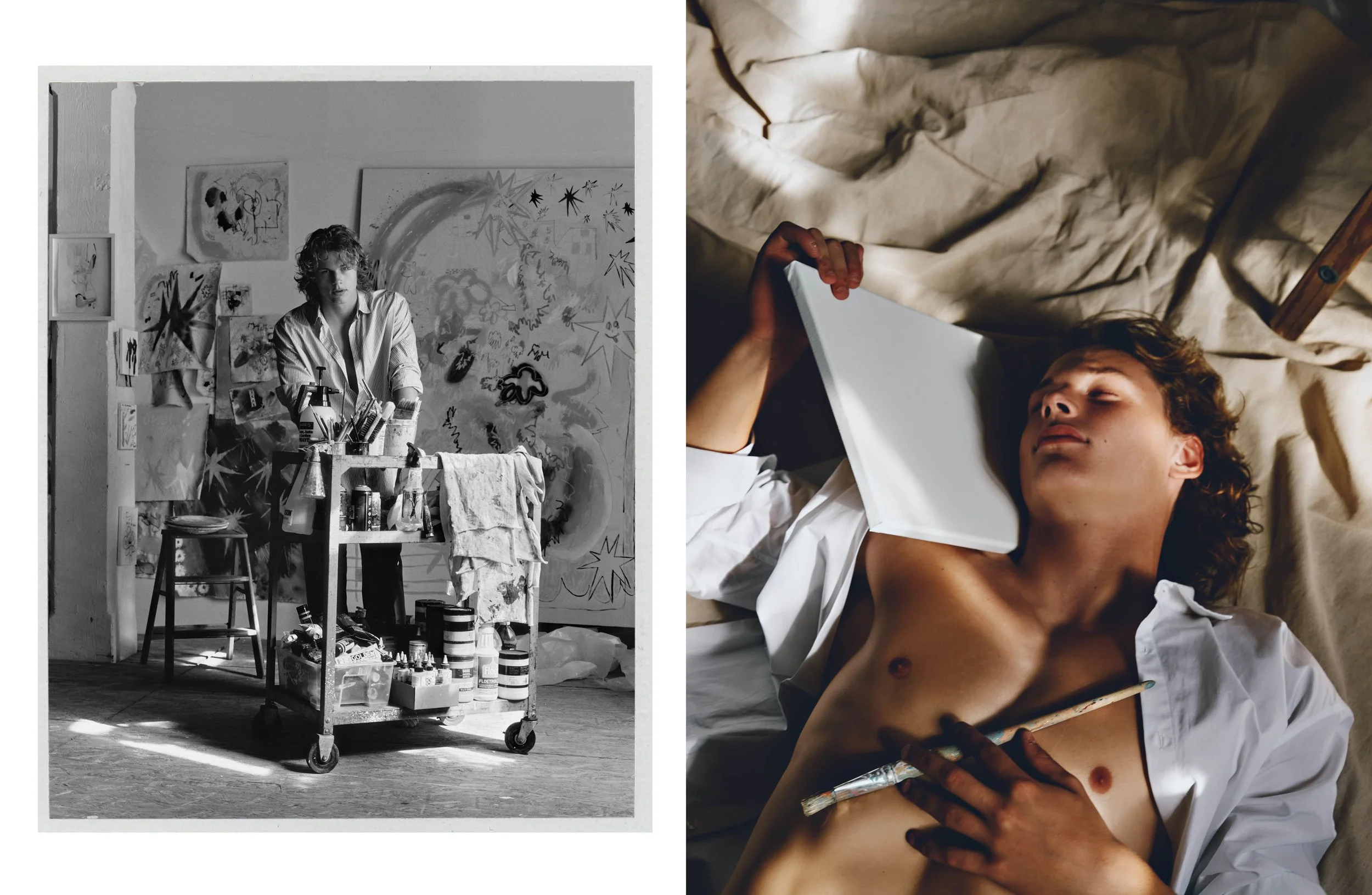

THEIR SHARED ROUTE WAS PART PILGRIMAGE, PART CREATIVE EXPERIMENT. FOR HOLZAPFEL, IT BECAME A WAY TO WEAVE THE PERSONAL INTO THE HISTORICAL – FOLDING THE RAW TEXTURES OF LIVED EXPERIENCE INTO HIS ONEIRIC PAINTINGS. SPEAKING FROM FRANKFURT BEFORE HIS UPCOMING MOVE TO LONDON, THE GERMAN ARTIST REFLECTS ON THE DELICATE BALANCE BETWEEN JOY AND GRIEF, WHY HE SEEKS DISCOMFORT TO KEEP HIS WORK ALIVE, AND THE ENDURING CHALLENGE OF MAKING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL VISIBLE.

Hi, how’s it going? I like your polo shirt!

Thank you. It’s perfect for summer. It’s so warm here, I just need something airy.

Tell me about the trip you and Hadar took and how it came to be.

Hadar had been wanting to take a trip to Europe for a long time, but was always caught up with work. I convinced him it was the right time — work will always be there, so he should just book the ticket. His main reason for visiting was to trace his family roots. His ancestors were from Greece, but most of them were killed in Auschwitz. Only his grandmother survived; she later moved to America.

He wanted to visit where they were from, and we also went to Auschwitz. I’m working on a new body of work dealing with the Holocaust, so it was important for me to go there, too. We decided to combine both our purposes for the trip. Since it was such a heavy subject, we also wanted to balance it with joy and creativity.

How long have you two known each other?

We met in New York two years ago when I was living there for a bit.

What do you enjoy about working with him?

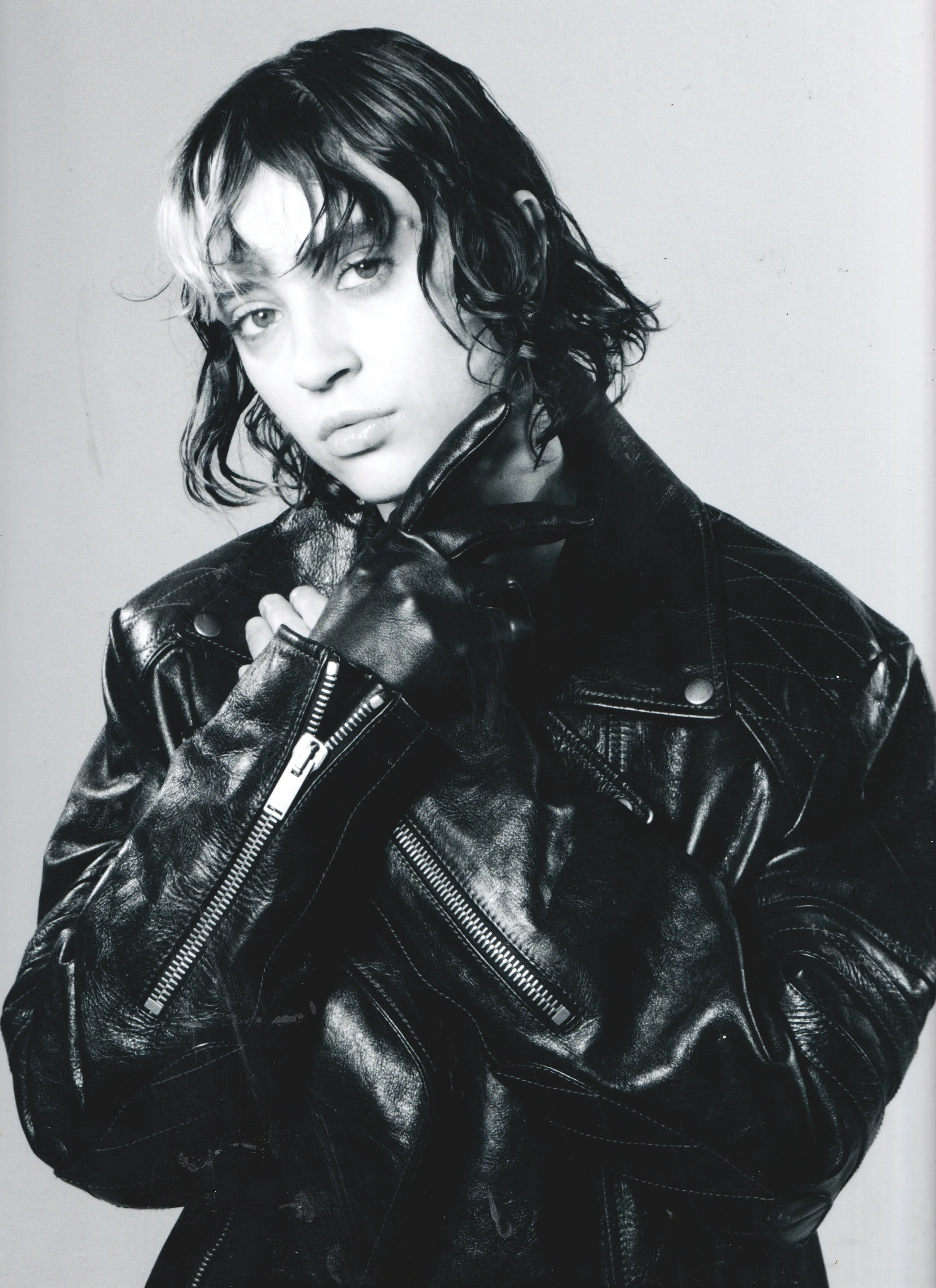

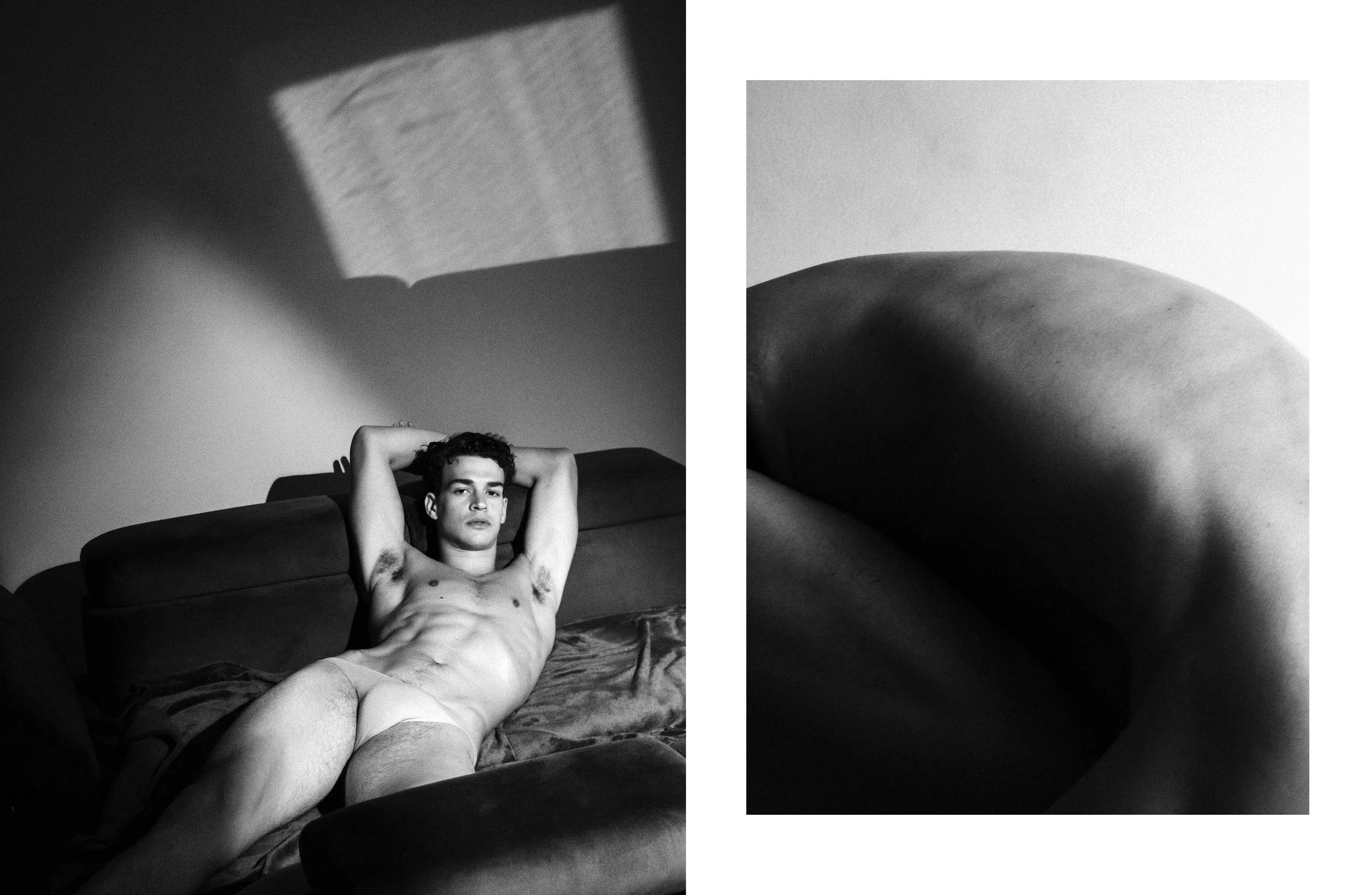

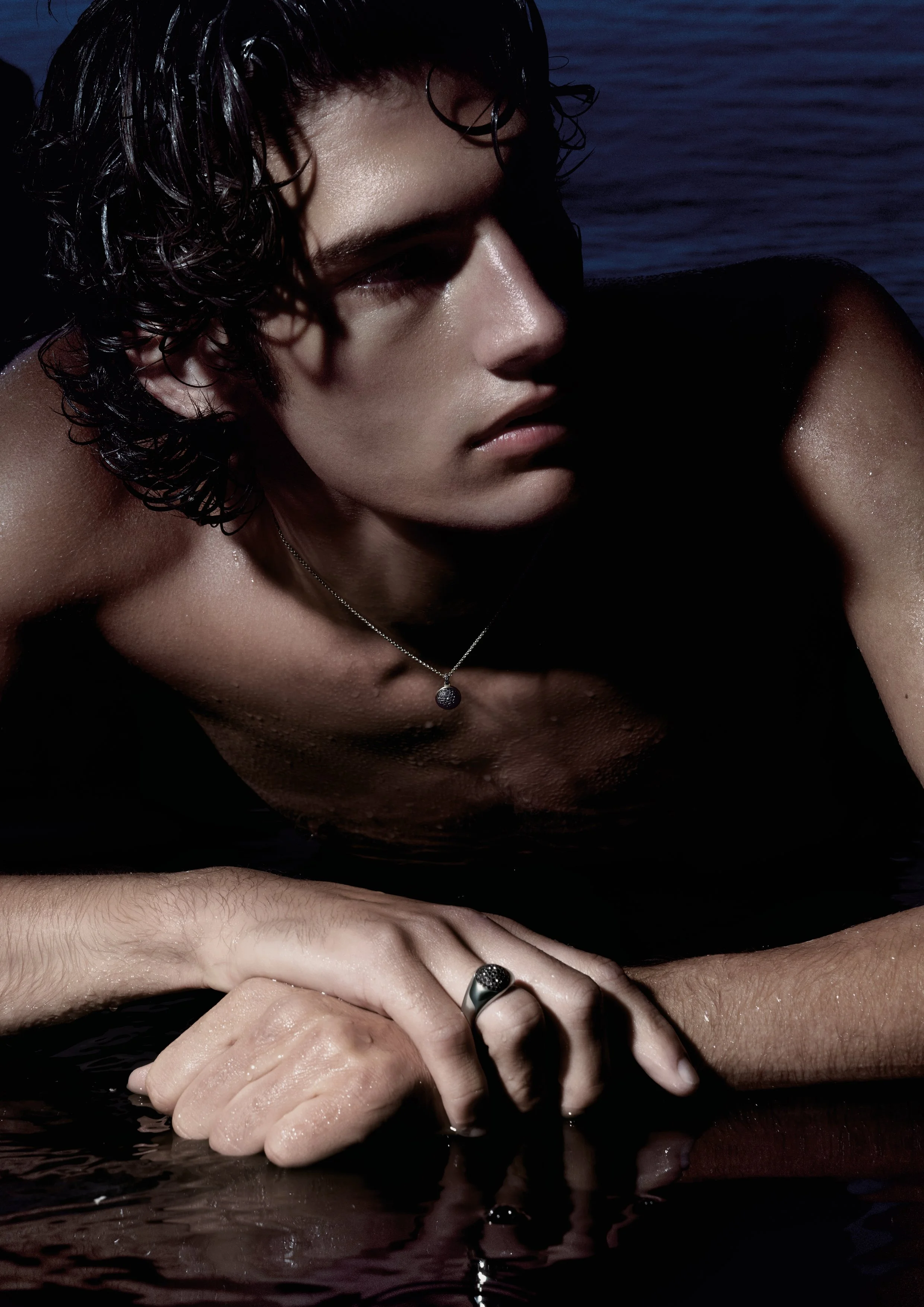

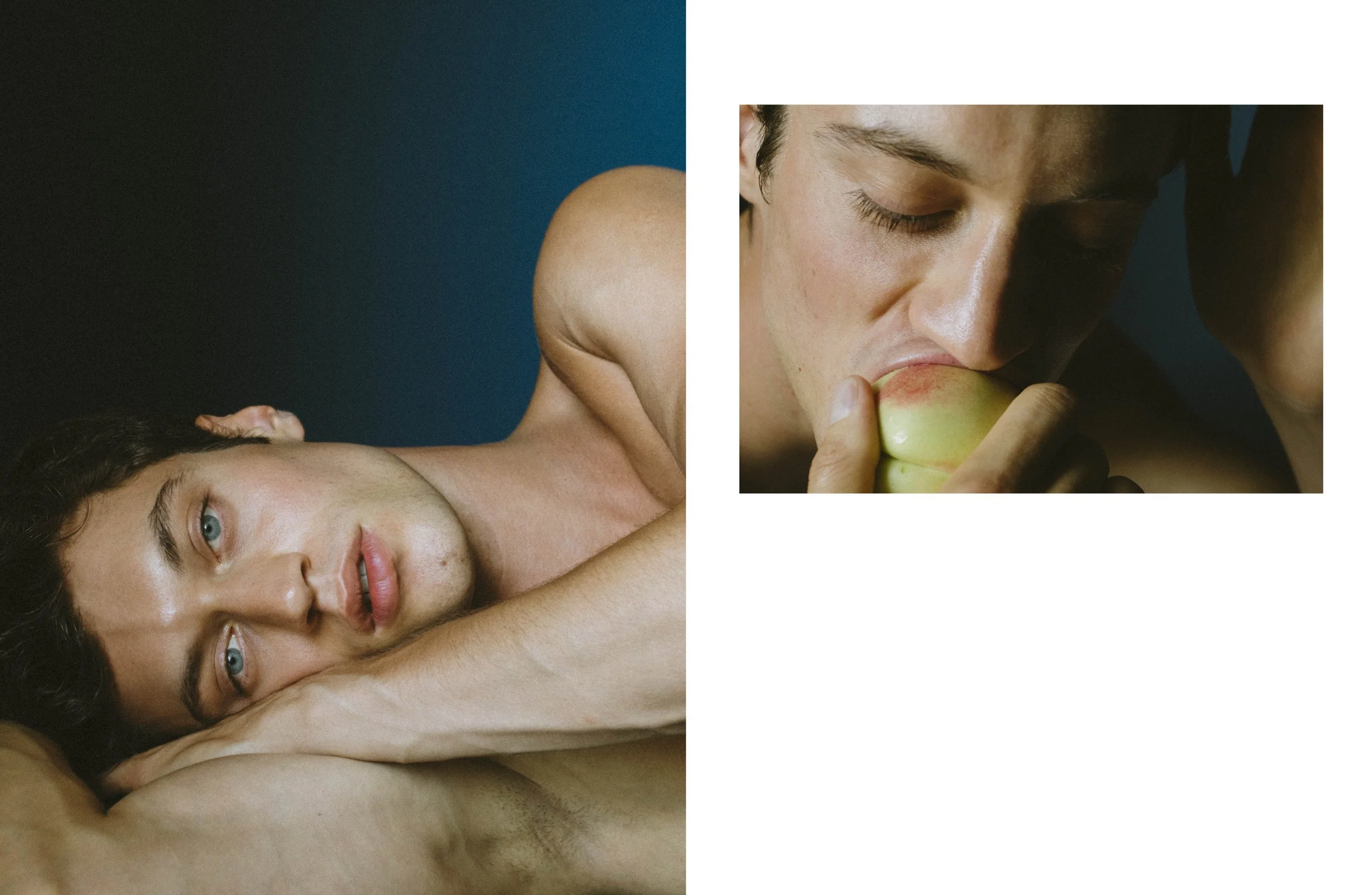

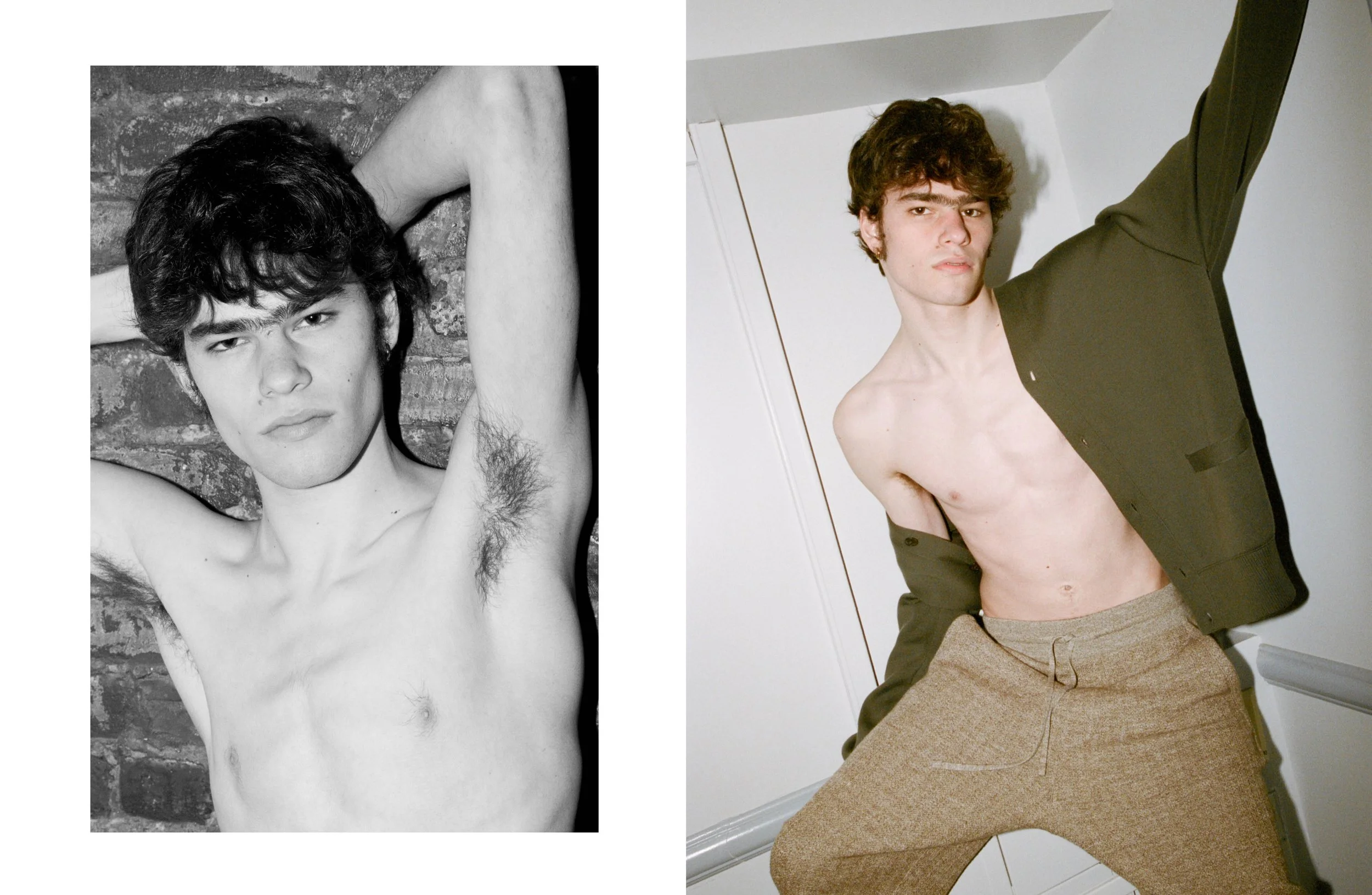

His process is very different. Before shooting, he spends a lot of time getting to know you — meeting once without the camera, then again to talk for an hour before taking any photos. His work is very intimate. One shoot lasted seven hours — I was exhausted, and that’s when the best images happened, because I stopped posing and just existed.

Was there a location from the trip that you especially loved?

Definitely Naxos, a Greek island. We stayed in an Airbnb that looked like a pink castle — surrounded by the classic white Greek houses. It had been in the owner’s family for 300 years. They used to grow and sell fruit, and even though it’s no longer profitable, they kept the garden. I’d wake up and pick apricots, lemons, and figs — it felt like paradise.

Auschwitz is the total opposite of that feeling. How did that visit influence your work?

My work usually focuses on myself, but with the last Holocaust survivors ageing, I feel it’s important to address this history — especially as a German. I interviewed a survivor to prepare, but I wanted to visit the place itself as well.

The most overwhelming moment was walking from where the trains arrived at Auschwitz II to the crematorium. Over a million people walked that path to their deaths. The most surprising thing was the field of flowers growing next to the crematorium — life springing from a place of death. That duality is something I want to bring into my paintings.

Growing up in Germany, how did you engage with this history?

You’re confronted with it early. In many German cities, there are memorial stones in the streets naming Holocaust victims. I also attended a Jewish primary school, so it was part of my daily environment. The survivor I interviewed is a family friend, so the topic has always felt close to me.

What was it like interviewing her?

She didn’t speak about her experiences until 1996, over 40 years later. Now she sees it as her life’s mission to educate younger generations, giving talks almost daily. She still dreams about it — it will never leave her.

You’ve said art is a form of therapy for you. When did you realise that?

I started painting two years ago. At first, my work was more political, but I didn’t feel deeply connected to it. After moving from New York to Amsterdam, I started channelling my emotions directly into my paintings. It was harder, because it’s personal, but also more fulfilling.

And what’s a work of art that’s inspired you in that way?

A self-portrait by Egon Schiele. He explored himself not just physically, but psychologically, bringing the inner into the outer. That’s what I try to do as well.

You seem to move around a lot. Where are you based now?

I’m staying with my parents until I move to London in September for my Master’s at Central Saint Martins. It’ll be the first time I have a proper studio and work alongside other artists.

I studied there too! It’s a world of its own.

I’m looking forward to that community, but I also like keeping one foot outside the art world to stay open to different perspectives.

What excites you about London?

I’ve missed a certain roughness and unpredictability in other cities that I’ve lived in, such as Amsterdam. London has that, and I think it’ll push me creatively.

Well, good luck — and I hope to see your degree show in two years.

Thank you. If you’re ever in London, send me a message.

Interview by Martin Onufrowicz

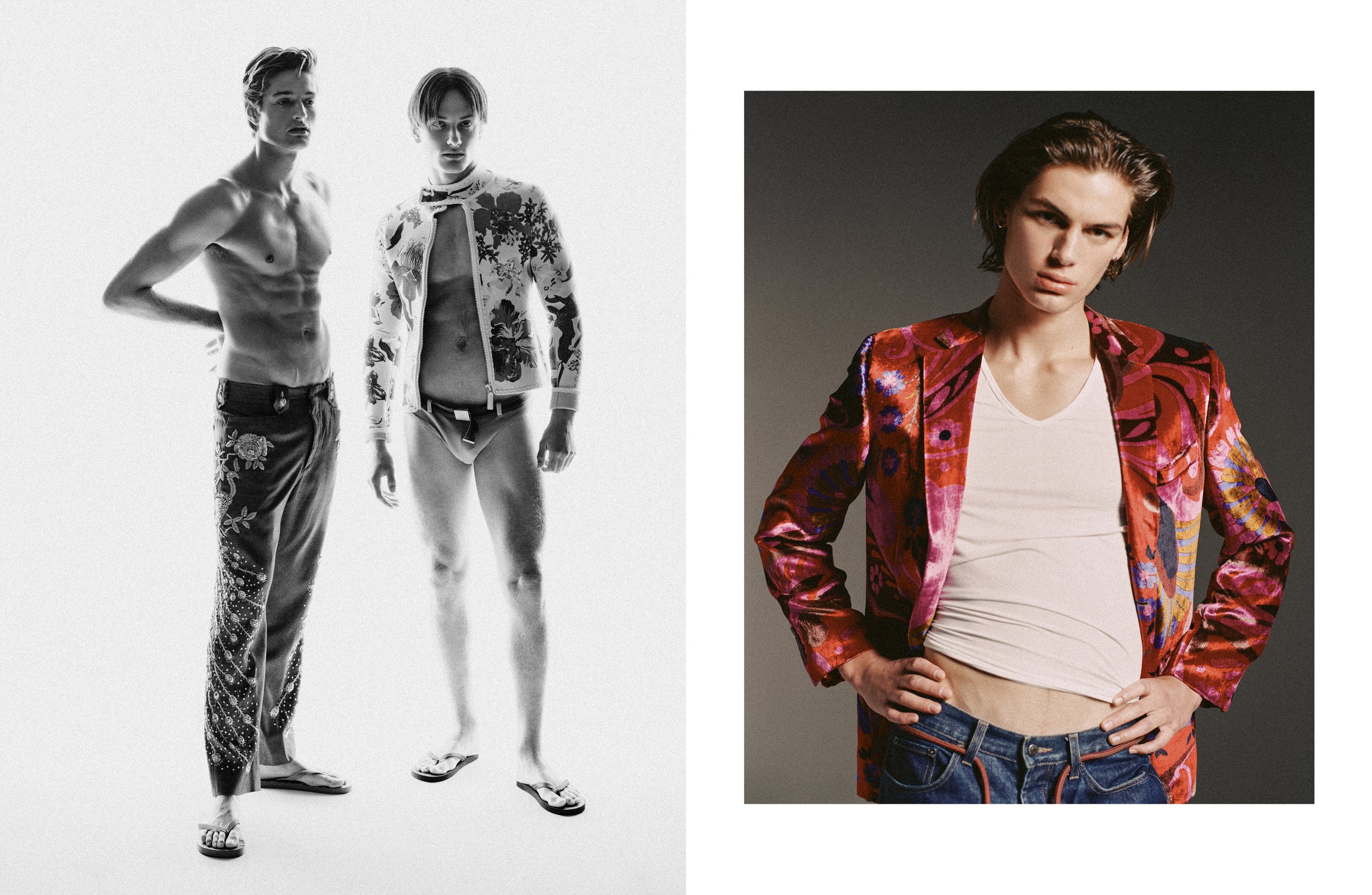

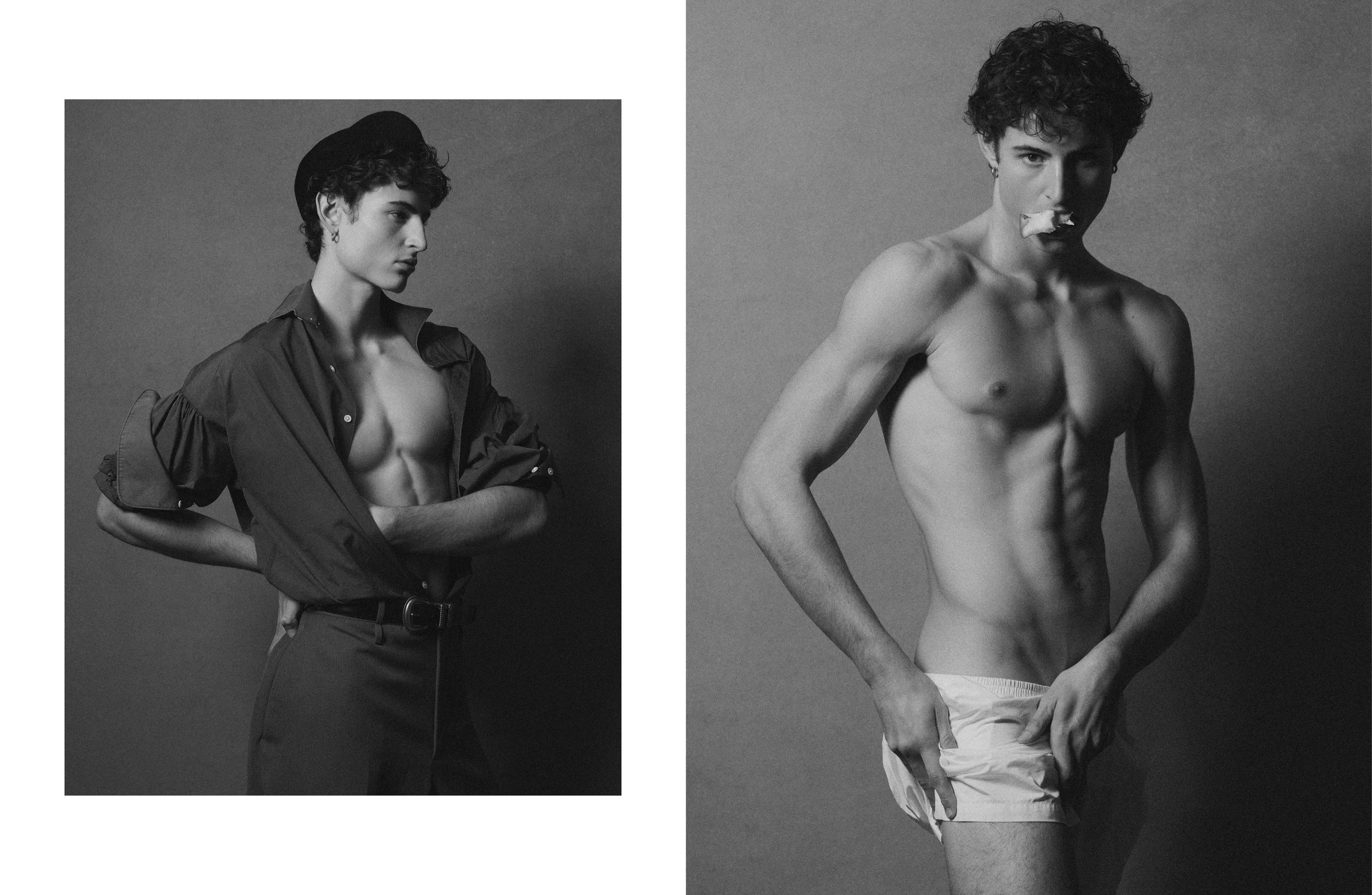

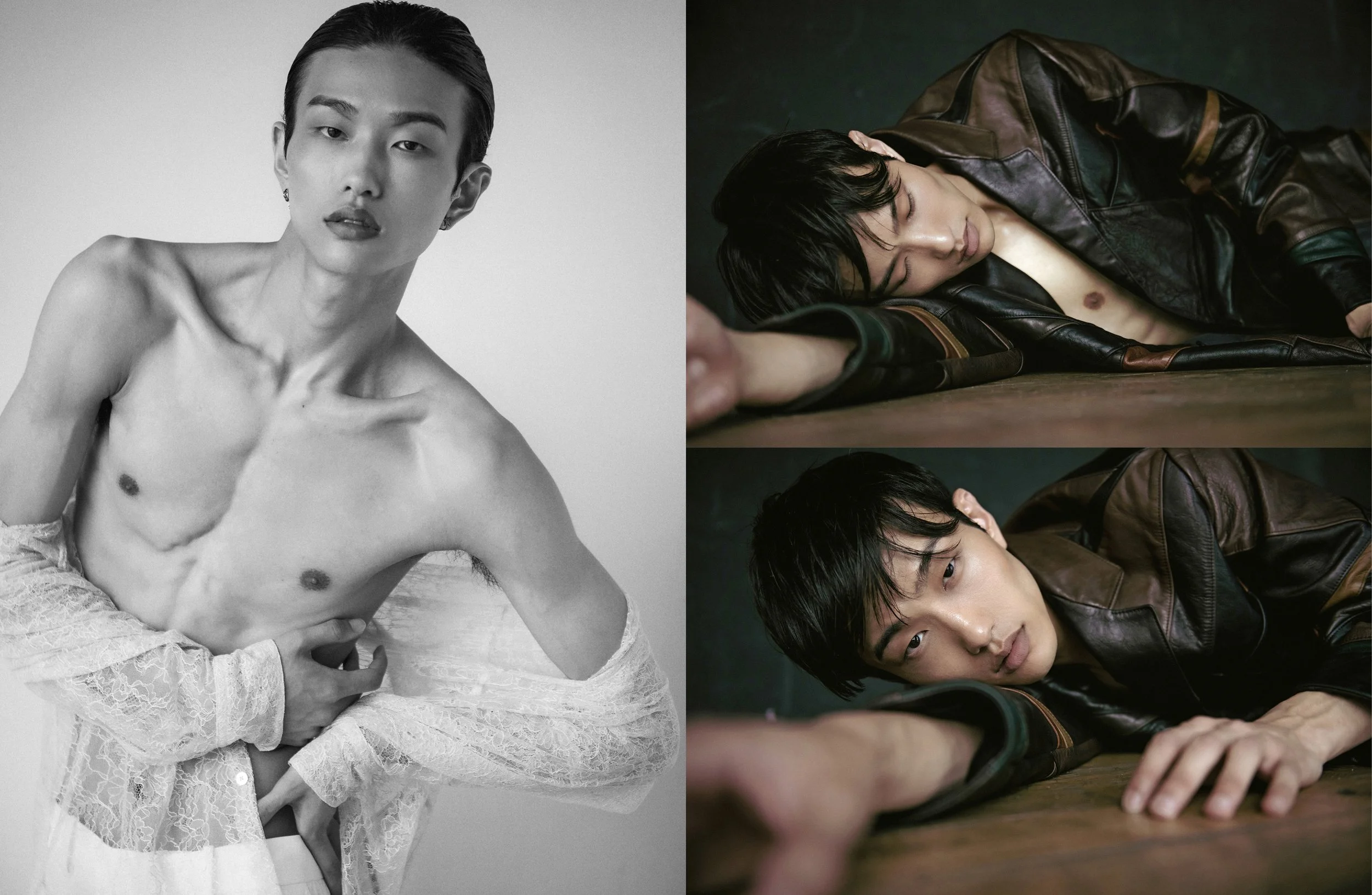

Photography by Hadar Pitchon