Closed for renovations since April 2018, Antwerp’s ModeMuseum, also known as MoMu, has finally reopened its doors. Thanks to Kaat Debo, who has been the museum’s director and curator for almost two decades, MoMu has cemented the privileged relationship Antwerp has with fashion, culture, history and innovation.

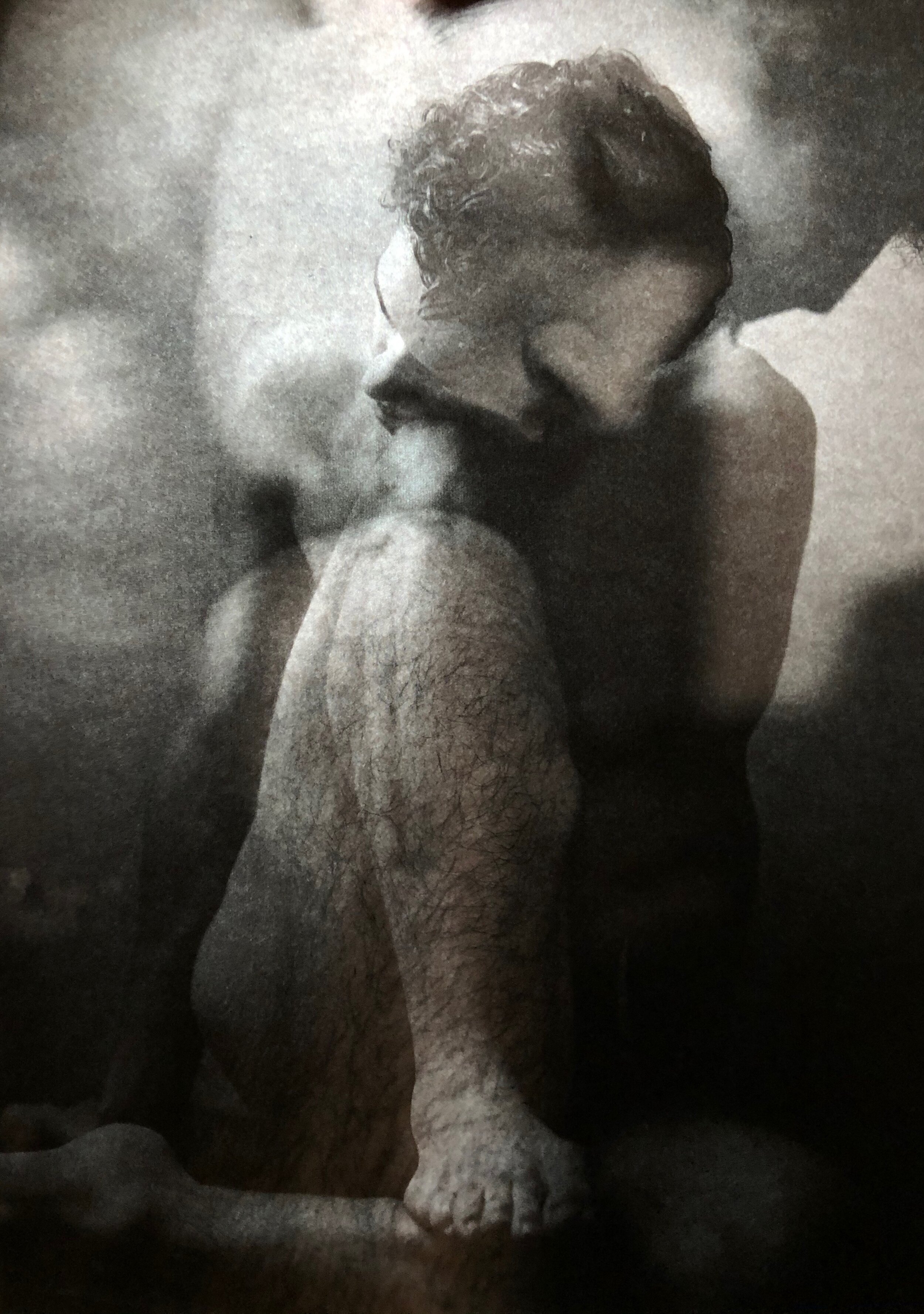

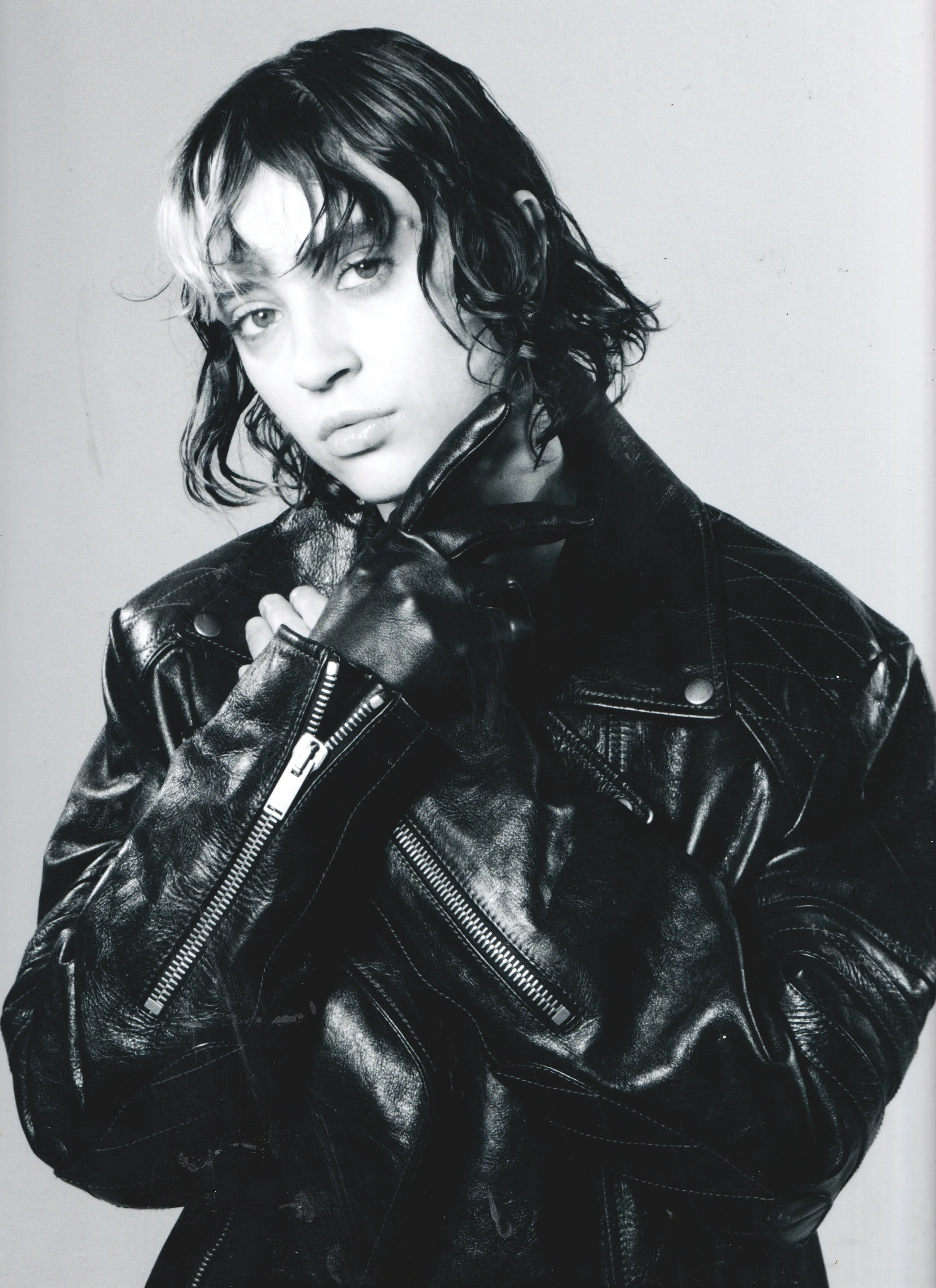

Debo isn’t your typical curator, and she loves to push the envelope with exhibitions that are often surprising, compelling and original. ‘E/MOTION. Fashion in transition’ opened this weekend and presents fashion as an illustration of our fears, longing and desires.

We sat down with Debo to discuss renovation during a pandemic, the importance of emotion in her work and how she shops designer collections as a museum curator.

Renovating a museum within a pandemic outbreak must have been challenging. How did you deal with this?

3 years sounds like a long time, but as the renovation itself was complex, it was in fact quite a short period for such a task. The pandemic affected everything of course, starting with the preparation of the new exhibition. Most fashion houses were focused on saving their businesses and delivering on time, so we were not a priority for them. It was very difficult to get the loans we wanted, and for the books we were working on, some photographers could not access their archives anymore due to the lockdown. The building itself was delayed due to shortage of materials, until quite recently. That was challenging.

Guess calling it a ‘labor of love’ is not an exaggeration then.

At the same time, I don’t want to complain, because I know how tough it has been for other museums that were open and had to change their rules constantly, losing considerable income as well. In that sense, the timing was not bad for a renovation, it was just difficult to do it.

“I don’t think you can separate emotion from fashion.”

.

Did COVID-19 influence your exhibition planning in any way?

We had started working on ‘E/MOTION. Fashion in transition’ before the pandemic started, but when it came to the direction of the exhibition itself, I really wanted something that reflected the moment we were in and the challenges designers had been facing. If you look at the past three decades, they show the growth and evolution of globalization, which affected fashion in a really strong way, so the idea was to reflect on the big transformative moments taking place over the past 30 years, from economic recession and political turmoil to global terrorism and different kinds of health crises.

Emotion is an important part of what you create as a museum director and curator. How do you see its relationship to the fashion world?

I don’t think you can separate emotion from fashion. Faced with COVID-19, designers had to find new ways to communicate their storytelling digitally as opposed to physically, and that meant finding alternatives to the traditional show format. This search for new ways was very interesting for me, as well as trying to figure out what the place of real emotion would be within the industry today. We wanted physical presence in the exhibition through performance, which is new within that context. We thought it’d be wonderful to have a human presence after months spent behind computer screens.

Some brands continued doing shows even after the pandemic started. Did that feel strange to you? Can things be exactly the same as they were before?

Well, I did find it a bit strange as well. Digital allowed many designers to be innovative and find successful ways to communicate with their audiences. This doesn’t mean that everyone was successful doing it, but the possibilities of digital are huge.

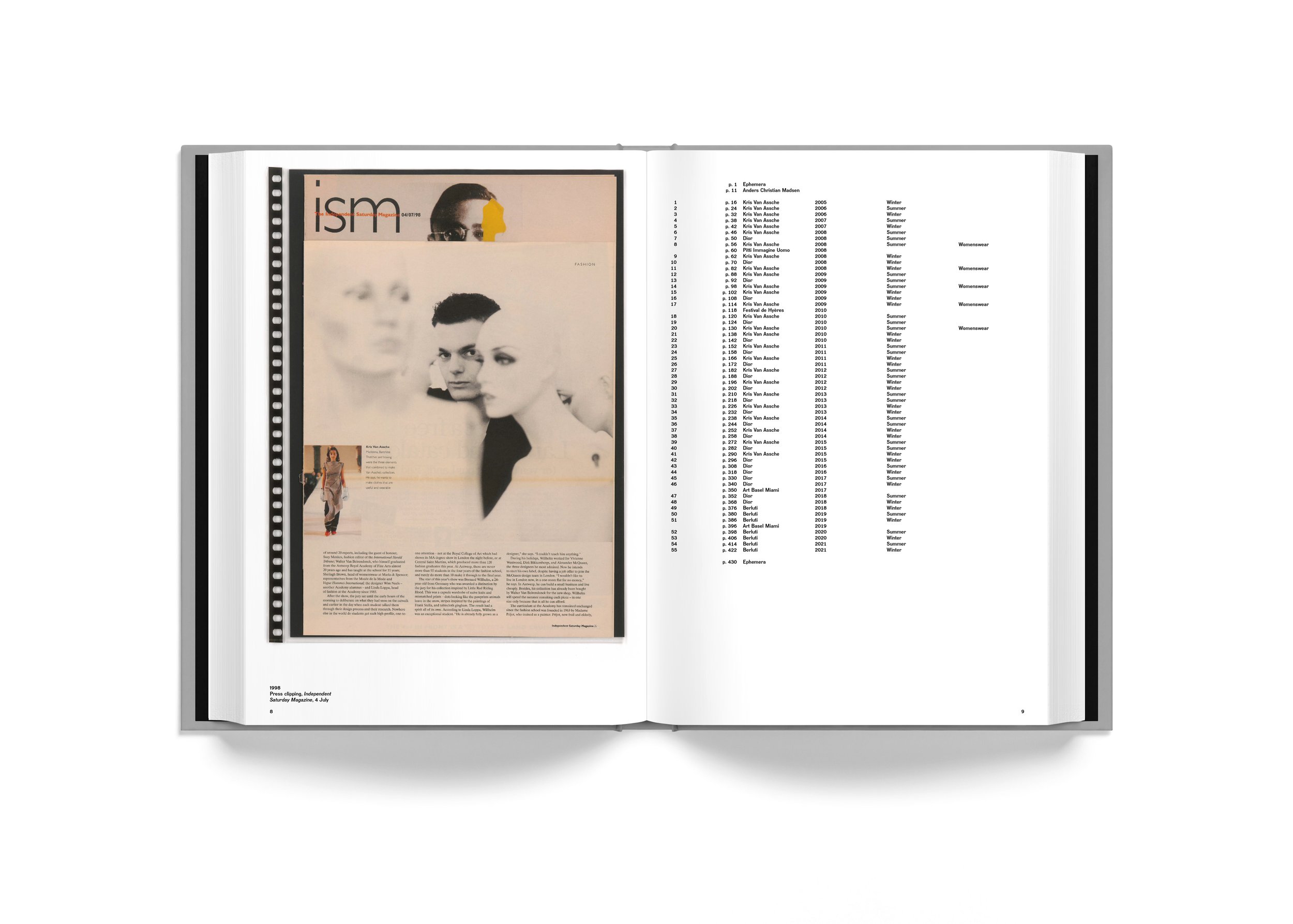

I’ve wanted to ask you this for a long time: how do you keep up with the changes at major fashion houses, where designers seem to come and go? Does this make your job harder as a curator?

That is one of the biggest challenges when you collect contemporary fashion as a museum. It’s very difficult to decide in the moment whether something is relevant or has historical importance. A curator should be able to enjoy some kind of critical distance and space for reflection, but fashion doesn’t allow you to do that. You need to decide immediately what pieces to buy and don’t have the luxury of waiting for another 6 months. Most of our purchasing takes place during the show period, which is quite complicated. What we acquire as a museum should not only reflect the times we’re living in, but also present a designer’s signature, as well as express political and societal changes. It is true that creative directors come and go at a rapid pace, which means that, as a museum, we also have the responsibility to document this, even though it’s quite a recent phenomenon within the industry itself.

…

Kaat Debo was interviewed by Philippe Pourhashemi